UNITED STATES

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

FORM 6-K

REPORT OF FOREIGN PRIVATE ISSUER

PURSUANT TO RULE 13a-16 OR 15d-16

UNDER THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934

For the month of November 2025

Commission File Number: 001-13184

TECK RESOURCES LIMITED

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter)

Suite 3300 – 550 Burrard Street

Vancouver, British Columbia V6C 0B3

(Address of principal executive offices)

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant files or will file annual reports under cover of Form 20-F or Form 40-F.

Form 20-F ¨ Form 40-F x Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto duly authorized.

EXHIBIT INDEX

| Exhibit Number |

Description |

| 99.1 | NI 43-101 Technical Report Teck Highland Valley Copper; July 1, 2025 |

SIGNATURE

| Teck Resources Limited | ||

| (Registrant) | ||

| Date: November 10, 2025 | By: | /s/ Amanda R. Robinson |

| Amanda R. Robinson | ||

| Corporate Secretary | ||

Exhibit 99.1

NI 43-101 Technical Report on

Highland Valley Copper Operations

British Columbia

Prepared For:

Teck Resources Limited

Prepared By:

Mr. Christopher Hercun, P.Eng.

Mr. Alex Stewart, P.Geo.

Mr. Tim Tsuji, P.Eng.

Mr. Frank Laroche, P.Eng.

Mr. Carl Diederichs, P.Eng.

Effective Date:

1 July, 2025

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

I, Christopher Hercun, P.Eng., am employed as the Superintendent, Strategic Planning, Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership, with a site address at Highland Valley Rd, Logan Lake, B.C. Canada, VOK 1WO.

This certificate applies to the technical report titled “NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations, British Columbia” that has an effective date of 1 July, 2025 (the “technical report”).

I am a Professional Engineer of Engineers and Geoscientists British Columbia; License Number 41498. I graduated from Montana Technological University with a degree in Mining Engineering in 2010.

I have practiced my profession for fifteen years. I have been directly involved in various operational roles at Teck. Relevant experience includes mine planning, geology, geometallurgy, closure planning, project engineering and management, risk management, environmental studies, permitting, economic analysis and business planning.

As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43–101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43–101) for those sections of the technical report that I am responsible for preparing.

I work at the Highland Valley Copper Operations on a daily basis, and this familiarity with the operation serves as my scope of personal inspection.

I am responsible for Sections 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.6, 1.9, 1.17 (excepting tailings storage), 1.18, 1.19, 1.20, 1.21, 1.22, 1.23, 1.24, 1.25; Sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4.1, 2.5, 2.6, 2.7; Section 3; Section 4; Section 5; Section 6; Section 12.3.1; Section 18 (excepting 18.6); Section 19; Section 20; Section 21; Section 22; Section 24; Sections 25.1, 25.2, 25.3, 25.12 (excepting tailings storage), 25.13, 25.14, 25.15, 25.16, 25.17, 25.18, 25.19; Section 26; Section 27; and Appendix A of the technical report.

I am not independent of Teck Resources Limited, as independence is described by Section 1.5 of NI 43–101.

I have been involved with the Highland Valley Copper Operations since 2013.

I have read NI 43–101 and the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible have been prepared in compliance with that Instrument.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

As of the effective date of the technical report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible contain all scientific and technical information that is required to be disclosed to make those sections of the technical report not misleading.

Dated this 10th day of November 2025.

“signed and sealed”

Christopher Hercun, P.Eng.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

I, Alex Stewart, P.Geo., am employed as the Senior Mine Geostatistician, with the Highland Valley Copper Partnership, with a site address at Highland Valley Rd, Logan Lake, B.C. Canada, VOK 1WO.

This certificate applies to the technical report titled “NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations, British Columbia” that has an effective date of 1 July, 2025 (the “technical report”).

I am a Professional Geoscientist (P.Geo.) with Engineers and Geoscientists BC #42690. I graduated from the Lakehead University with an Honours Bachelor of Science degree in Geology in 1995.

I have practiced my profession for 30 years. I have been directly involved in mining operations, mineral resource and mineral reserve estimation, and analysis at open-pit and underground mines within Canada. I have experience in exploration, drilling program definition, geological mapping, interpretation and modeling, geometallurgical programs, grade estimation, grade control and mine to mill reconciliation.

As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43–101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43–101) for those sections of the technical report that I am responsible for preparing.

I work at the Highland Valley Copper Operations on a daily basis, and this familiarity with the operation serves as my scope of personal inspection.

I am responsible for Sections 1.1, 1.2, 1.5, 1.6, 1.7, 1.8, 1.9, 1.11, 1.12; Sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4.2, 2.5, 2.6, 2.7; Section 3; Section 7; Section 8; Section 9; Section 10; Section 11; Sections 12.1, 12.2, 12.3.2; Section 14; Section 23; Sections 25.1, 25.4, 25.5, 25.6, 25.8; Section 26; and Section 27 of the technical report.

I am not independent of Teck Resources Limited, as independence is described by Section 1.5 of NI 43–101.

I have been involved with the Highland Valley Copper Operations since 2011.

I have read NI 43–101 and the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible have been prepared in compliance with that Instrument.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

As of the effective date of the technical report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible contain all scientific and technical information that is required to be disclosed to make those sections of the technical report not misleading.

Dated this 10th day of November 2025.

“signed and sealed”

Alex Stewart, P.Geo.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

I, Tim Tsuji, P.Eng., am employed as the Chief Mine Engineer, Strategic Planning, Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership, with a site address at Highland Valley Rd, Logan Lake, B.C. Canada, VOK 1WO.

This certificate applies to the technical report titled “NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations, British Columbia” that has an effective date of 1 July, 2025 (the “technical report”).

I am a Professional Engineer of Engineers and Geoscientists British Columbia; License Number 37762. I graduated from the University of British Columbia with a Bachelor of Applied Science degree in Mining and Mineral Processing Engineering (Mining Option) in 2000.

I have practiced my profession for 21 years. I have been directly involved in mine design and mine planning at Highland Valley Copper for 13 years and Mineral Reserve and Mineral Resource estimation for 11 of those years.

As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43–101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43–101) for those sections of the technical report that I am responsible for preparing.

I work at the Highland Valley Copper Operations on a daily basis, and this familiarity with the operation serves as my scope of personal inspection.

I am responsible for Sections 1.1, 1.2, 1.9. 1.13, 1.14, 1.15 (except geotechnical and hydrogeological); Sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4.3, 2.5; Section 3; Section 12.3.3; Section 15; Sections 16.1, 16.4, 16.5, 16.6, 16.7, 16.8, 16.9, 16.10, 16.11; Sections 25.1, 25.6, 25.9, 25.10; Section 26; and Section 27 of the technical report.

I am not independent of Teck Resources Limited, as independence is described by Section 1.5 of NI 43–101.

I have been involved with the Highland Valley Copper Operations since 2012.

I have read NI 43–101 and the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible have been prepared in compliance with that Instrument.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

As of the effective date of the technical report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible contain all scientific and technical information that is required to be disclosed to make those sections of the technical report not misleading.

Dated this 10th day of November 2025.

“signed and sealed”

Tim Tsuji, P.Eng.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

I, Frank Laroche, P.Eng, am employed as the Principal Engineer Mineral Processing, Strategic Planning North America, Teck Resources Limited, with an office address at Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3.

This certificate applies to the technical report titled “NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations, British Columbia” that has an effective date of 1 July, 2025 (the “technical report”).

I am a Professional Engineer (P.Eng) registered with Engineers and Geoscientists of British Columbia (EGBC); License Number 55606. I graduated from McGill University with a bachelor's degree in Materials Engineering in 2008.

I have practiced my profession for 17 years. I have been directly involved in site visits and inspected all current stages of mineral processing, including crushing, grinding, flotation, leaching, and dewatering. I’ve contributed to geometallurgical programs through sample selection, managing test work and data analysis. I’m directly involved in the design and ongoing reconciliation of the copper recovery and throughput modeling.

As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43–101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43–101) for those sections of the technical report that I am responsible for preparing.

I work at the Highland Valley Copper Operations on a daily basis, and this familiarity with the operation serves as my scope of personal inspection.

I am responsible for Sections 1.1, 1.2, 1.9, 1.10, 1.16; Sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4.4; Section 3; Section 12.3.4; Section 13; Section 17; Sections 25.1, 25.7, 25.11; Section 26; and Section 27 of the technical report.

I am not independent of Teck Resources Limited, as independence is described by Section 1.5 of NI 43–101.

I have been involved with the Highland Valley Copper Operations since 2008.

I have read NI 43–101 and the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible have been prepared in compliance with that Instrument.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

As of the effective date of the technical report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible contain all scientific and technical information that is required to be disclosed to make those sections of the technical report not misleading.

Dated this 10th day of November 2025.

“signed and sealed”

Frank Laroche, P.Eng.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

CERTIFICATE OF QUALIFIED PERSON

I, Carl Diederichs, P.Eng., am employed as the Superintendent, Geotechnical, Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership, with a site address at Highland Valley Rd, Logan Lake, B.C. Canada, VOK 1WO.

This certificate applies to the technical report titled “NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations, British Columbia” that has an effective date of 1 July, 2025 (the “technical report”).

I am a Professional Engineer of Engineers and Geoscientists British Columbia; License Number 39796. I graduated from Geological Engineering at the University of British Columbia in 2008.

I have practiced my profession for seventeen years since graduation. I have been directly involved in engineering design, planning and operations at Highland Valley Copper Operations between 2008–-2010 and 2012–current.

As a result of my experience and qualifications, I am a Qualified Person as defined in National Instrument 43–101 Standards of Disclosure for Mineral Projects (NI 43–101) for those sections of the technical report that I am responsible for preparing.

I work at the Highland Valley Copper Operations on a daily basis, and this familiarity with the operation serves as my scope of personal inspection.

I am responsible for Sections 1.1, 1.2, 1.15 (geotechnical and hydrogeological only), 1.17 (tailings storage only); Sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4.5; Section 3; Section 12.3.5; Sections 16.2, 16.3; Section 18.6; Sections 25.1, 25.6, 25.12 (tailings storage only); Section 26; and Section 27 of the technical report.

I am not independent of Teck Resources Limited, as independence is described by Section 1.5 of NI 43–101.

I have been involved with the Highland Valley Copper Operations since 2008.

I have read NI 43–101 and the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible have been prepared in compliance with that Instrument.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

As of the effective date of the technical report, to the best of my knowledge, information and belief, the sections of the technical report for which I am responsible contain all scientific and technical information that is required to be disclosed to make those sections of the technical report not misleading.

Dated this 10th day of November 2025.

“signed and sealed”

Carl Diederichs, P.Eng.

Teck Resources Limited

Suite 3300, Bentall 5, 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C0B3

www.teck.com

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

Table Of Contents

| 1 | SUMMARY | 1-1 |

| 1.1 | Introduction | 1-1 |

| 1.2 | Terms of Reference | 1-1 |

| 1.3 | Project Setting | 1-1 |

| 1.4 | Mineral Tenure, Surface Rights, Water Rights, Royalties and Agreements | 1-2 |

| 1.5 | Geology and Mineralization | 1-3 |

| 1.6 | History | 1-4 |

| 1.7 | Drilling | 1-5 |

| 1.8 | Sampling and Analysis | 1-6 |

| 1.9 | Data Verification | 1-7 |

| 1.10 | Metallurgical Testwork | 1-7 |

| 1.11 | Mineral Resource Estimation | 1-8 |

| 1.12 | Mineral Resources Statement | 1-10 |

| 1.13 | Mineral Reserve Estimation | 1-12 |

| 1.14 | Mineral Reserves Statement | 1-13 |

| 1.15 | Mining Methods | 1-13 |

| 1.16 | Recovery Methods | 1-15 |

| 1.17 | Project Infrastructure | 1-17 |

| 1.18 | Markets and Contracts | 1-20 |

| 1.19 | Environmental, Permitting and Social Considerations | 1-21 |

| 1.19.1 | Environmental Considerations | 1-21 |

| 1.19.2 | Closure and Reclamation Planning | 1-21 |

| 1.19.3 | Permitting Considerations | 1-22 |

| 1.19.4 | Social Considerations | 1-22 |

| 1.20 | Capital Cost Estimates | 1-23 |

| 1.21 | Operating Cost Estimates | 1-23 |

| 1.22 | Economic Analysis | 1-24 |

| 1.23 | Risks and Opportunities | 1-25 |

| 1.23.1 | Risks | 1-25 |

| 1.23.2 | Opportunities | 1-25 |

| 1.24 | Interpretation and Conclusions | 1-25 |

| 1.25 | Recommendations | 1-26 |

| 2 | INTRODUCTION | 2-1 |

| 2.1 | Introduction | 2-1 |

| 2.2 | Terms of Reference | 2-1 |

| 2.3 | Qualified Persons | 2-4 |

| 2.4 | Site Visits and Scope of Personal Inspection | 2-4 |

| 2.4.1 | Mr. Christopher Hercun | 2-4 |

| 2.4.2 | Mr. Alex Stewart | 2-4 |

| 2.4.3 | Mr. Tim Tsuji | 2-4 |

| 2.4.4 | Mr. Frank Laroche | 2-5 |

| 2.4.5 | Mr. Carl Diederichs | 2-5 |

| 2.5 | Effective Dates | 2-5 |

| 2.6 | Information Sources and References | 2-5 |

| 2.7 | Previous Technical Reports | 2-6 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| 3 | RELIANCE ON OTHER EXPERTS | 3-1 |

| 4 | PROPERTY DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION | 4-1 |

| 4.1 | Introduction | 4-1 |

| 4.2 | Ownership | 4-1 |

| 4.3 | Mineral Tenure | 4-1 |

| 4.4 | Surface Rights | 4-1 |

| 4.5 | Water Rights | 4-7 |

| 4.6 | Royalties | 4-7 |

| 4.7 | Permitting Considerations | 4-7 |

| 4.8 | Environmental Considerations | 4-7 |

| 4.9 | Social Considerations | 4-7 |

| 4.10 | QP Comment on Item 4 “Property Description and Location” | 4-7 |

| 5 | ACCESSIBILITY, CLIMATE, LOCAL RESOURCES, INFRASTRUCTURE AND PHYSIOGRAPHY | 5-1 |

| 5.1 | Accessibility | 5-1 |

| 5.2 | Climate | 5-1 |

| 5.3 | Local Resources and Infrastructure | 5-2 |

| 5.4 | Physiography and Land Use | 5-2 |

| 5.5 | Seismicity | 5-3 |

| 5.6 | Sufficiency of Surface Rights | 5-3 |

| 6 | HISTORY | 6-1 |

| 6.1 | Ownership, Exploration, and Development History | 6-1 |

| 6.2 | Production History | 6-1 |

| 7 | GEOLOGICAL SETTING AND MINERALIZATION | 7-1 |

| 7.1 | Regional Geology | 7-1 |

| 7.2 | Project Geology | 7-1 |

| 7.2.1 | Lithologies | 7-1 |

| 7.2.2 | Structure | 7-4 |

| 7.2.3 | Metamorphism and Alteration | 7-4 |

| 7.2.4 | Mineralization | 7-4 |

| 7.3 | Deposit Descriptions | 7-6 |

| 7.3.1 | Valley Deposit | 7-6 |

| 7.3.2 | Lornex Deposit | 7-13 |

| 7.3.3 | Highmont Deposit | 7-17 |

| 7.3.4 | Bethlehem Deposit | 7-24 |

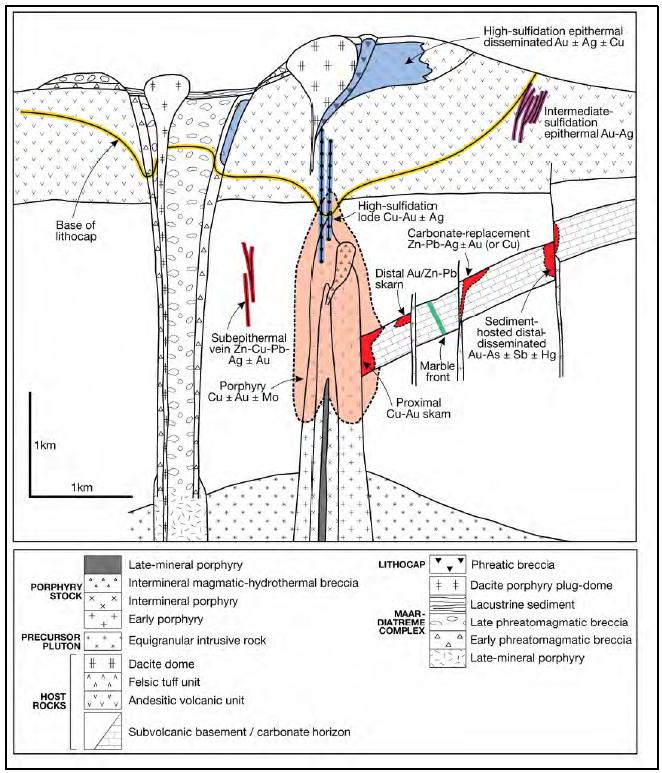

| 8 | DEPOSIT TYPES | 8-1 |

| 8.1 | Introduction | 8-1 |

| 8.2 | Deposit Type Description | 8-1 |

| 8.2.1 | Geological Setting | 8-1 |

| 8.2.2 | Mineralization | 8-2 |

| 8.2.3 | Alteration | 8-2 |

| 8.3 | QP Comment on Item 8 “Deposit Types” | 8-4 |

| 9 | EXPLORATION | 9-1 |

| 9.1 | Grids and Surveys | 9-1 |

| 9.2 | Geological Mapping | 9-1 |

| 9.3 | Geochemical Sampling | 9-2 |

| 9.4 | Geophysics | 9-2 |

| 9.4.1 | Airborne Surveys | 9-2 |

| 9.4.2 | Ground Surveys | 9-2 |

| 9.5 | Petrology, Mineralogy, and Research Studies | 9-4 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| 9.6 | Exploration Potential | 9-5 |

| 9.6.1 | Near-Mine Potential | 9-5 |

| 9.6.2 | Regional Potential | 9-5 |

| 10 | DRILLING | 10-1 |

| 10.1 | Introduction | 10-1 |

| 10.2 | Drill Methods | 10-1 |

| 10.2.1 | Reverse Circulation Drilling | 10-1 |

| 10.2.2 | Core Drilling | 10-1 |

| 10.3 | Logging Procedures | 10-11 |

| 10.4 | Recovery | 10-11 |

| 10.5 | Collar Surveys | 10-12 |

| 10.6 | Downhole Surveys | 10-12 |

| 10.7 | Grade Control | 10-13 |

| 10.8 | Sample Length/True Thickness | 10-13 |

| 10.9 | Drilling Completed Since Database Close-out Date | 10-13 |

| 10.10 | QP Comment on Item 10 “Drilling” | 10-15 |

| 11 | SAMPLE PREPARATION, ANALYSES, AND SECURITY | 11-1 |

| 11.1 | Sample Methods | 11-1 |

| 11.1.1 | Geochemical Sampling | 11-1 |

| 11.1.2 | Reverse Circulation Drill Sampling | 11-1 |

| 11.1.3 | Core Sampling | 11-1 |

| 11.1.4 | Blast Hole Sampling | 11-2 |

| 11.2 | Density Determinations | 11-3 |

| 11.3 | Analytical and Test Laboratories | 11-3 |

| 11.4 | Sample Preparation | 11-4 |

| 11.5 | Analysis | 11-5 |

| 11.6 | Quality Assurance and Quality Control | 11-5 |

| 11.7 | Databases | 11-11 |

| 11.8 | Sample Security | 11-12 |

| 11.9 | Sample Storage | 11-12 |

| 11.10 | QP Comment on Item 11 “Sample Preparation, Analyses and Security” | 11-12 |

| 12 | DATA VERIFICATION | 12-1 |

| 12.1 | Internal Data Verification | 12-1 |

| 12.1.1 | Data Verification and Quality Assurance | 12-1 |

| 12.1.2 | Process Audits and Independent Reviews | 12-1 |

| 12.2 | External Data Verification | 12-1 |

| 12.3 | Verification by Qualified Persons | 12-2 |

| 12.3.1 | Mr. Christopher Hercun | 12-2 |

| 12.3.2 | Mr. Alex Stewart | 12-2 |

| 12.3.3 | Mr. Tim Tsuji | 12-4 |

| 12.3.4 | Mr. Frank Laroche | 12-4 |

| 12.3.5 | Mr. Carl Diederichs | 12-5 |

| 13 | MINERAL PROCESSING AND METALLURGICAL TESTING | 13-1 |

| 13.1 | Introduction | 13-1 |

| 13.2 | Metallurgical Testwork | 13-1 |

| 13.2.1 | Mineralogical and Liberation Analyses | 13-3 |

| 13.2.2 | Comminution Testwork | 13-3 |

| 13.2.3 | Flotation Testwork | 13-3 |

| 13.2.4 | Mill Design | 13-10 |

| 13.3 | Recovery Estimates | 13-10 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| 13.4 | Metallurgical Variability | 13-13 |

| 13.5 | Deleterious Elements | 13-13 |

| 14 | MINERAL RESOURCE ESTIMATES | 14-1 |

| 14.1 | Introduction | 14-1 |

| 14.2 | Valley | 14-1 |

| 14.2.1 | Lithologies | 14-1 |

| 14.2.2 | Modelling Approach | 14-1 |

| 14.2.3 | Exploratory Data Analysis | 14-4 |

| 14.2.4 | Density Assignment | 14-7 |

| 14.2.5 | Composites | 14-7 |

| 14.2.6 | Grade Capping/Outlier Restrictions | 14-7 |

| 14.2.7 | Variography | 14-7 |

| 14.2.8 | Estimation/Interpolation Methods | 14-8 |

| 14.2.9 | Validation | 14-12 |

| 14.2.10 | Classification of Mineral Resources | 14-12 |

| 14.2.11 | Cut-off Criteria | 14-13 |

| 14.3 | Lornex | 14-14 |

| 14.3.1 | Lithologies | 14-14 |

| 14.3.2 | Modelling Approach | 14-14 |

| 14.3.3 | Exploratory Data Analysis | 14-14 |

| 14.3.4 | Density Assignment | 14-19 |

| 14.3.5 | Composites | 14-19 |

| 14.3.6 | Grade Capping/Outlier Restrictions | 14-19 |

| 14.3.7 | Variography | 14-19 |

| 14.3.8 | Estimation/Interpolation Methods | 14-19 |

| 14.3.9 | Validation | 14-24 |

| 14.3.10 | Classification of Mineral Resources | 14-24 |

| 14.3.11 | Cut-off Criteria | 14-24 |

| 14.4 | Highmont | 14-25 |

| 14.4.1 | Lithologies | 14-25 |

| 14.4.2 | Modelling Approach | 14-25 |

| 14.4.3 | Exploratory Data Analysis | 14-30 |

| 14.4.4 | Density Assignment | 14-30 |

| 14.4.5 | Composites | 14-30 |

| 14.4.6 | Grade Capping/Outlier Restrictions | 14-30 |

| 14.4.7 | Variography | 14-30 |

| 14.4.8 | Estimation/Interpolation Methods | 14-31 |

| 14.4.9 | Validation | 14-31 |

| 14.4.10 | Classification of Mineral Resources | 14-31 |

| 14.4.11 | Cut-off Criteria | 14-35 |

| 14.5 | Bethlehem | 14-35 |

| 14.5.1 | Lithologies | 14-35 |

| 14.5.2 | Modelling Approach | 14-35 |

| 14.5.3 | Exploratory Data Analysis | 14-39 |

| 14.5.4 | Density Assignment | 14-39 |

| 14.5.5 | Composites | 14-39 |

| 14.5.6 | Grade Capping/Outlier Restrictions | 14-43 |

| 14.5.7 | Variography | 14-43 |

| 14.5.8 | Estimation/Interpolation Methods | 14-44 |

| 14.5.9 | Validation | 14-45 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| 14.5.10 | Classification of Mineral Resources | 14-45 |

| 14.5.11 | Cut-off Criteria | 14-45 |

| 14.6 | Reasonable Prospects of Eventual Economic Extraction | 14-45 |

| 14.7 | Mineral Resources Statement | 14-46 |

| 14.8 | Factors That May Affect the Mineral Resources Estimate | 14-48 |

| 14.9 | QP Comment on Item 14 “Mineral Resource Estimates” | 14-48 |

| 15 | MINERAL RESERVE ESTIMATES | 15-1 |

| 15.1 | Introduction | 15-1 |

| 15.2 | Pit Optimization | 15-1 |

| 15.3 | Optimization Inputs | 15-1 |

| 15.4 | Cut-off Criteria | 15-2 |

| 15.5 | Ore Loss and Dilution | 15-2 |

| 15.6 | Stockpiles | 15-2 |

| 15.7 | Mineral Reserves Statement | 15-3 |

| 15.8 | Factors that May Affect the Mineral Reserves | 15-3 |

| 15.9 | QP Comment on Item 15 “Mineral Reserve Estimates” | 15-3 |

| 16 | MINING METHODS | 16-1 |

| 16.1 | Overview | 16-1 |

| 16.2 | Geotechnical Considerations | 16-1 |

| 16.3 | Hydrogeological Considerations | 16-1 |

| 16.3.1 | Valley Pit | 16-1 |

| 16.3.2 | Highmont Pit | 16-9 |

| 16.3.3 | Lornex Pit | 16-9 |

| 16.3.4 | Bethlehem Pits | 16-10 |

| 16.4 | Mine Designs | 16-10 |

| 16.5 | Stockpiles | 16-10 |

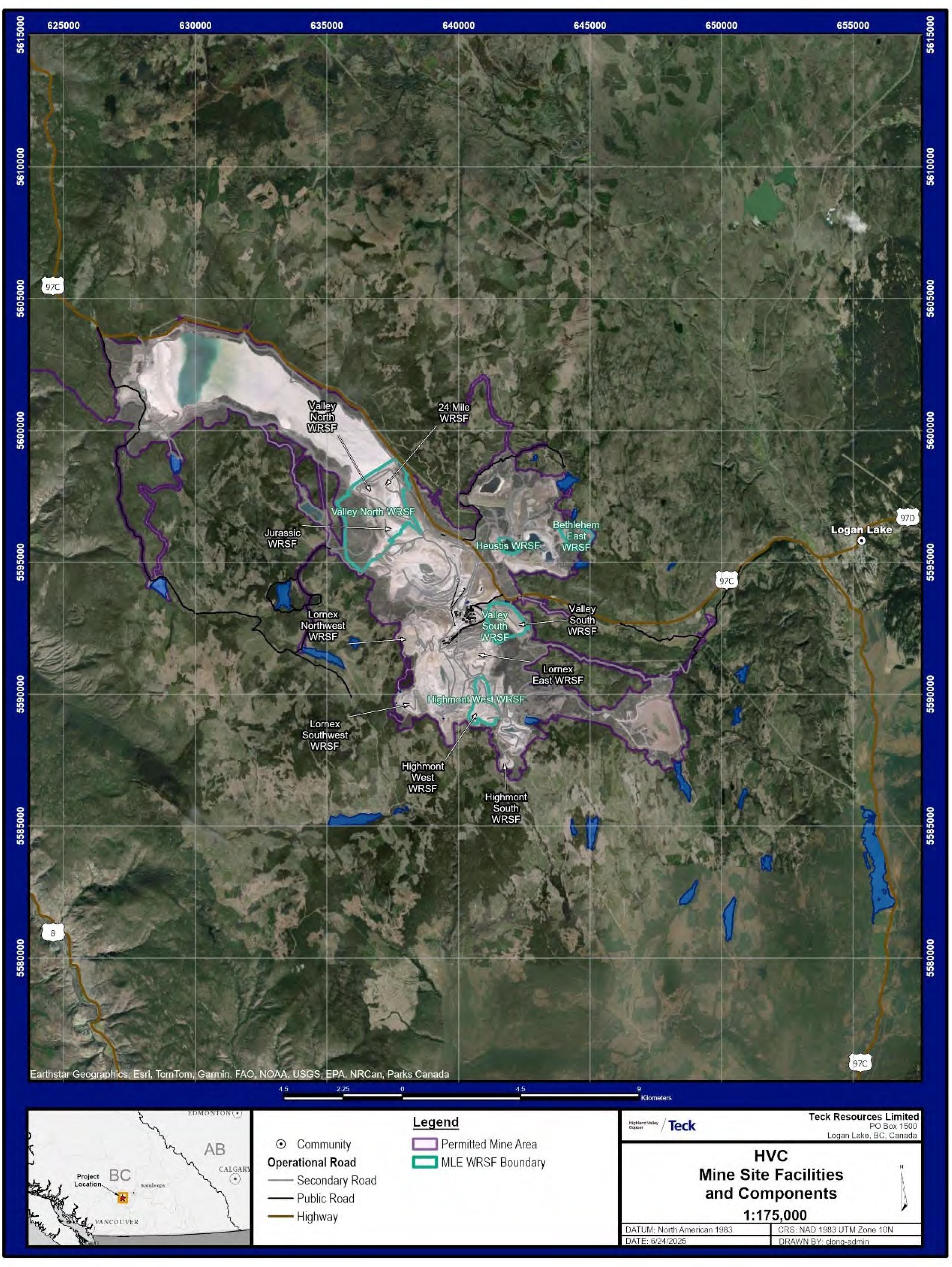

| 16.6 | Waste Rock Storage Facilities | 16-12 |

| 16.7 | Infrastructure | 16-14 |

| 16.8 | Life-Of-Mine Plan | 16-14 |

| 16.9 | Blasting and Explosives | 16-16 |

| 16.10 | Grade Control | 16-16 |

| 16.11 | Equipment | 16-16 |

| 17 | RECOVERY METHODS | 17-1 |

| 17.1 | Introduction | 17-1 |

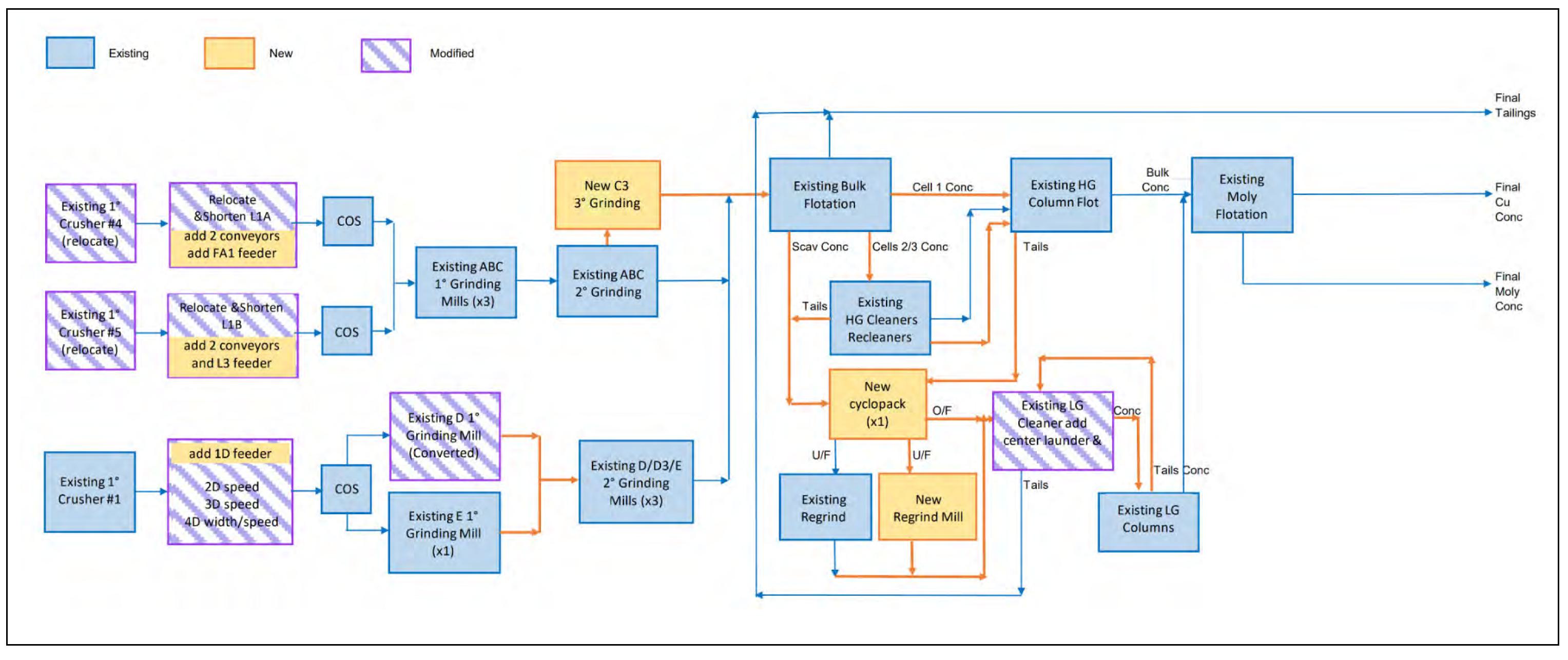

| 17.2 | Process Upgrades | 17-1 |

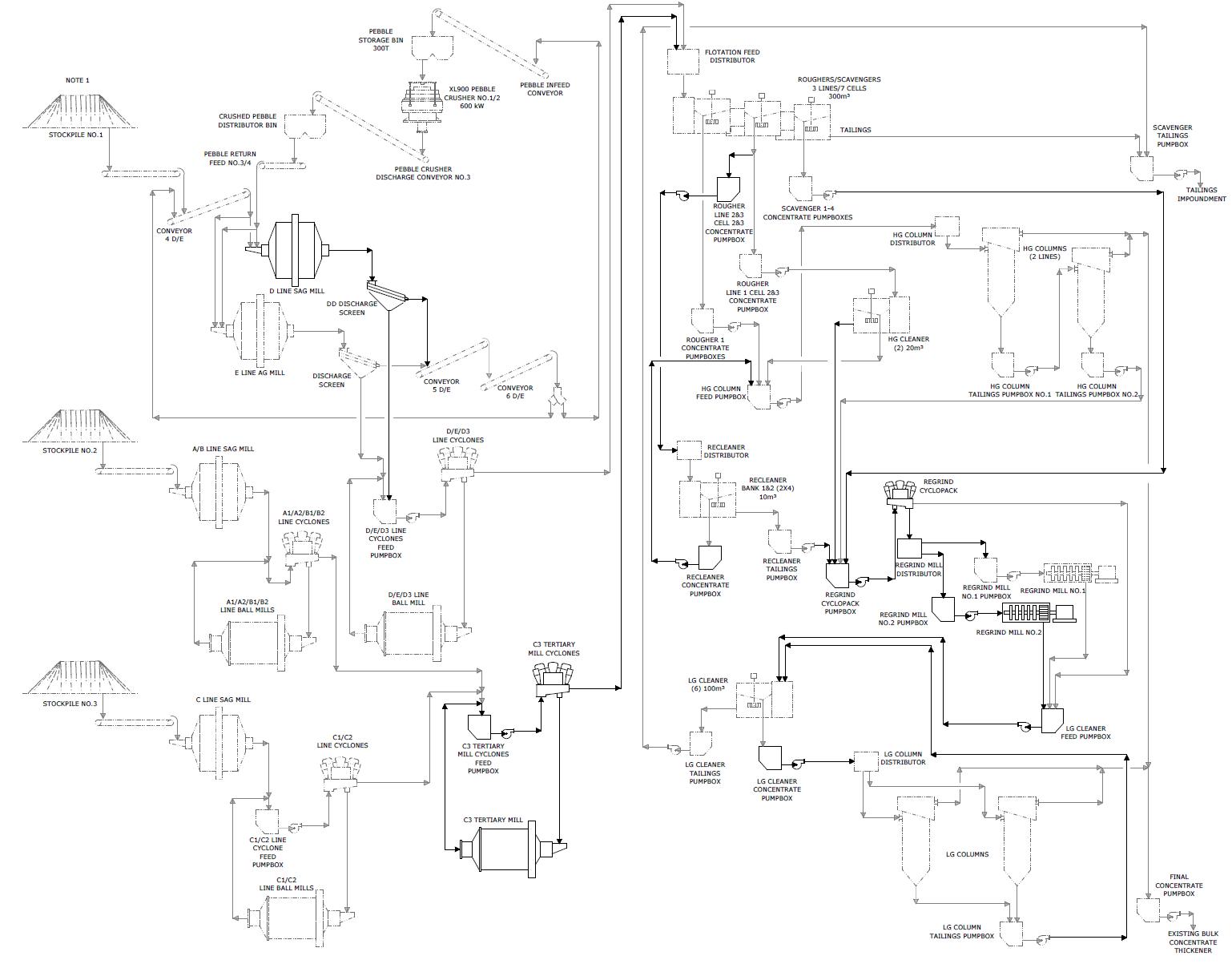

| 17.3 | Process Flow Sheet | 17-1 |

| 17.4 | Plant Design | 17-1 |

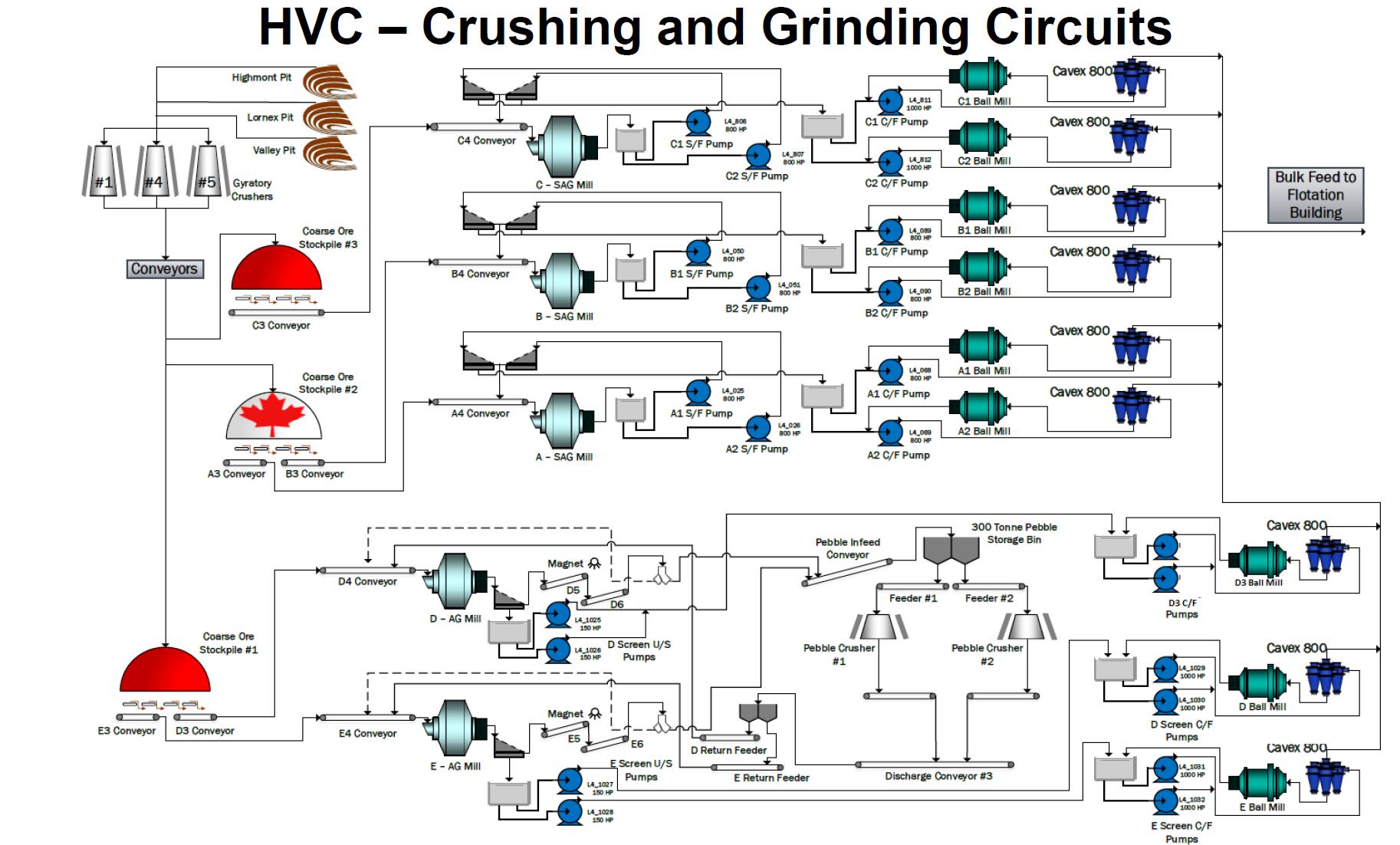

| 17.4.1 | Crushing and Material Handling | 17-7 |

| 17.4.2 | Grinding | 17-8 |

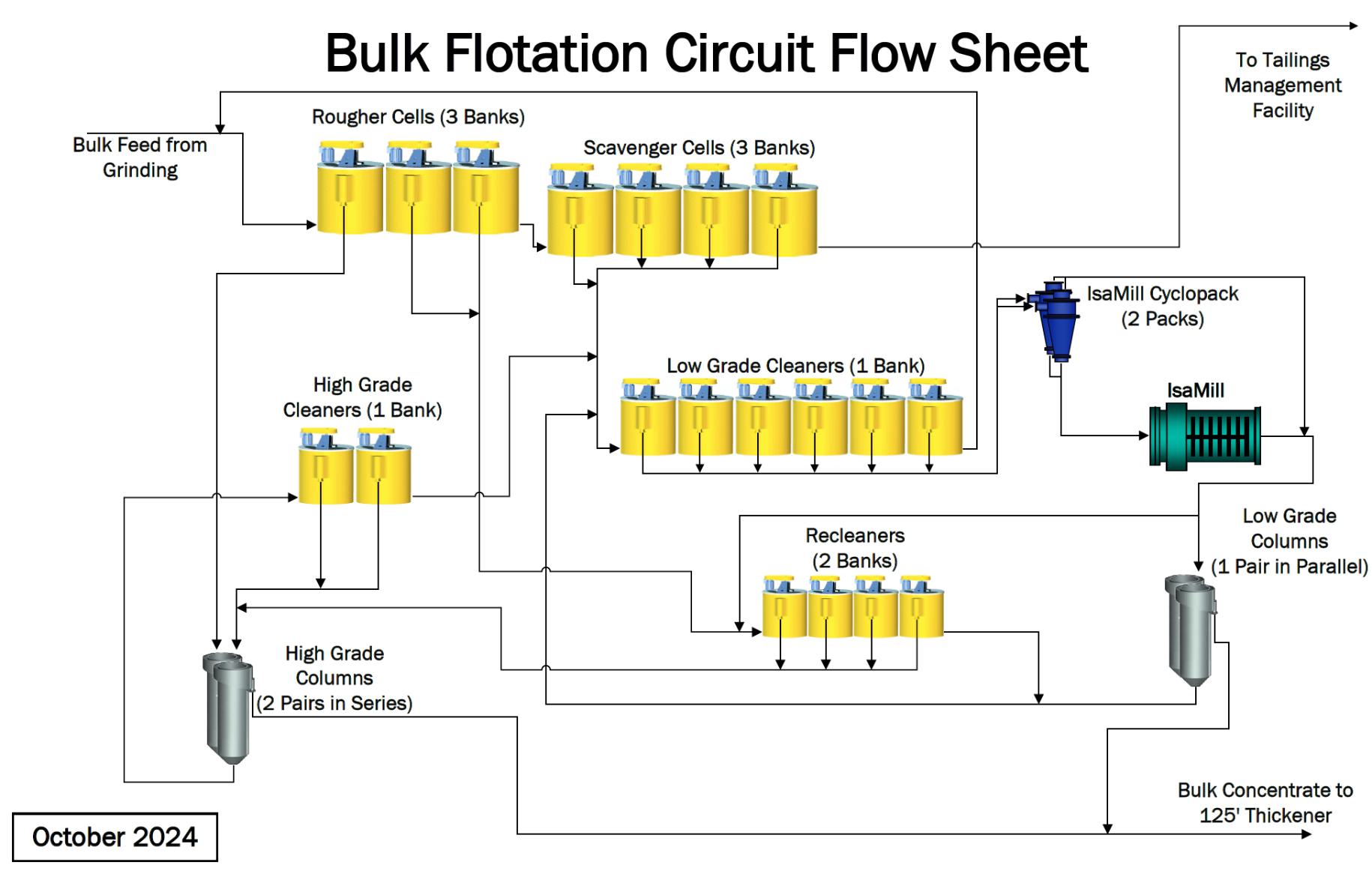

| 17.4.3 | Flotation and Regrind | 17-14 |

| 17.4.4 | Rougher and Scavenger Flotation | 17-15 |

| 17.4.5 | High-Grade Column Flotation | 17-17 |

| 17.4.6 | High-Grade Cleaners and Recleaners | 17-17 |

| 17.4.7 | Regrind Circuit | 17-18 |

| 17.4.8 | Low-Grade Column Flotation | 17-19 |

| 17.5 | Tailings System | 17-20 |

| 17.6 | Water Management | 17-21 |

| 17.7 | Process Control | 17-22 |

| 17.8 | Energy, Water, and Process Materials Requirements | 17-22 |

| 17.8.1 | Reagents and Consumables | 17-22 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| 17.8.2 | Water | 17-22 |

| 17.8.3 | Power | 17-23 |

| 18 | PROJECT INFRASTRUCTURE | 18-1 |

| 18.1 | Introduction | 18-1 |

| 18.1.1 | Current | 18-1 |

| 18.1.2 | LOM Plan | 18-2 |

| 18.2 | Road and Logistics | 18-2 |

| 18.3 | Geotechnical Studies In Support Of Infrastructure Designs | 18-2 |

| 18.4 | Stockpiles | 18-2 |

| 18.5 | Waste Rock Storage Facilities | 18-2 |

| 18.6 | Tailings Storage Facilities | 18-7 |

| 18.6.1 | Introduction | 18-7 |

| 18.6.2 | Highland TSF | 18-7 |

| 18.6.3 | LOM Plan | 18-7 |

| 18.7 | Water Supply | 18-10 |

| 18.7.1 | Current | 18-10 |

| 18.7.2 | LOM Plan | 18-10 |

| 18.8 | Water Management | 18-10 |

| 18.8.1 | Current | 18-10 |

| 18.8.2 | LOM Plan | 18-10 |

| 18.9 | Camps and Accommodation | 18-12 |

| 18.10 | Power and Electrical | 18-12 |

| 18.11 | Natural Gas | 18-13 |

| 19 | MARKET STUDIES AND CONTRACTS | 19-1 |

| 19.1 | Market Studies | 19-1 |

| 19.1.1 | Copper Demand | 19-1 |

| 19.1.2 | Copper Supply | 19-1 |

| 19.1.3 | Copper Concentrate Marketability | 19-2 |

| 19.1.4 | Molybdenum Demand | 19-3 |

| 19.1.5 | Molybdenum Supply | 19-4 |

| 19.1.6 | Molybdenum Concentrate Marketability | 19-4 |

| 19.2 | Commodity Price Projections | 19-5 |

| 19.3 | Contracts | 19-5 |

| 19.4 | QP Comment on Item 19 “Market Studies and Contracts” | 19-5 |

| 20 | ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES, PERMITTING, AND SOCIAL OR COMMUNITY IMPACT | 20-1 |

| 20.1 | Introduction | 20-1 |

| 20.2 | Baseline and Supporting Studies | 20-1 |

| 20.3 | Environmental Monitoring | 20-2 |

| 20.4 | Closure | 20-3 |

| 20.4.1 | Closure Plan | 20-3 |

| 20.4.2 | Closure Costs | 20-3 |

| 20.5 | Permitting | 20-4 |

| 20.6 | Considerations of Social and Community Impacts | 20-4 |

| 20.6.1 | Social Performance Standard | 20-4 |

| 20.6.2 | Indigenous Communities | 20-7 |

| 20.6.3 | Community Investment Program | 20-8 |

| 21 | CAPITAL AND OPERATING COSTS | 21-1 |

| 21.1 | Capital Cost Estimates | 21-1 |

| 21.2 | Operating Cost Estimates | 21-1 |

| 21.3 | Closure Costs | 21-2 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| 22 | ECONOMIC ANALYSIS | 22-1 |

| 23 | ADJACENT PROPERTIES | 23-1 |

| 24 | OTHER RELEVANT DATA AND INFORMATION | 24-1 |

| 25 | INTERPRETATION AND CONCLUSIONS | 25-1 |

| 25.1 | Introduction | 25-1 |

| 25.2 | Ownership | 25-1 |

| 25.3 | Mineral Tenure, Surface Rights, Water Rights, Royalties and Agreements | 25-1 |

| 25.4 | Geology and Mineralization | 25-1 |

| 25.5 | Drilling, and Sampling | 25-2 |

| 25.6 | Data Verification | 25-2 |

| 25.7 | Metallurgical Testwork | 25-3 |

| 25.8 | Mineral Resource Estimates | 25-3 |

| 25.9 | Mineral Reserve Estimates | 25-4 |

| 25.10 | Mining Methods | 25-4 |

| 25.11 | Recovery Methods | 25-4 |

| 25.12 | Infrastructure | 25-5 |

| 25.13 | Market Studies and Contracts | 25-5 |

| 25.14 | Environmental, Permitting and Social Considerations | 25-6 |

| 25.15 | Capital Cost Estimates | 25-6 |

| 25.16 | Operating Cost Estimates | 25-7 |

| 25.17 | Economic Analysis | 25-7 |

| 25.18 | Risks and Opportunities | 25-8 |

| 25.18.1 | Risks | 25-8 |

| 25.18.2 | Opportunities | 25-8 |

| 25.19 | Conclusions | 25-8 |

| 26 | RECOMMENDATIONS | 26-1 |

| 27 | REFERENCES | 27-1 |

List Of Tables

| Table 1-1: | Metallurgical Recovery and Concentrate Grade Forecasts | 1-9 |

| Table 1-2: | Mineral Resources Summary Table | 1-11 |

| Table 1-3: | Mineral Reserves Summary Table | 1-14 |

| Table 1-4: | Capital Cost Estimate Summary Table (C$M, nominal terms) | 1-24 |

| Table 1-5: | Operating Cost Estimate Summary Table (C$M, nominal terms) | 1-24 |

| Table 4-1: | Surface Rights Table | 4-3 |

| Table 4-2: | BC Water Licences | 4-8 |

| Table 6-1: | Ownership, Exploration and Development History | 6-2 |

| Table 6-2: | Production Table | 6-5 |

| Table 7-1: | Key Phases, Guichon Creek Batholith | 7-3 |

| Table 7-2: | Key Lithologies, Valley–Lornex Deposit | 7-7 |

| Table 7-3: | Major Faults, Valley–Lornex Deposit | 7-10 |

| Table 7-4: | Alteration Types, Valley–Lornex Deposit | 7-11 |

| Table 7-5: | Key Lithologies, Lornex Deposit | 7-14 |

| Table 7-6: | Alteration Types, Lornex Deposit | 7-16 |

| Table 7-7: | Key Lithologies, Highmont Deposit | 7-18 |

| Table 7-8: | Alteration Types, Highmont Deposit | 7-21 |

| Table 7-9: | Key Lithologies, Bethlehem Deposit | 7-26 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| Table 7-10: | Alteration Types, Bethlehem Deposit | 7-30 |

| Table 9-1: | Recent Ground Geophysical Surveys | 9-4 |

| Table 10-1: | Project Drill Summary Table | 10-2 |

| Table 10-2: | Drilling Supporting Mineral Resource Estimation, Valley Deposit | 10-4 |

| Table 10-3: | Drilling Supporting Mineral Resource Estimation, Lornex Deposit | 10-4 |

| Table 10-4: | Drilling Supporting Mineral Resource Estimation, Highmont | 10-4 |

| Table 10-5: | Drilling Supporting Mineral Resource Estimation, Bethlehem | 10-5 |

| Table 10-6: | Blast Hole Patterns | 10-14 |

| Table 10-7: | Drilled Versus True Thickness | 10-14 |

| Table 11-1: | Specific Gravity Summary Table | 11-4 |

| Table 11-2: | Analytical and Test Laboratories | 11-4 |

| Table 11-3: | Sample Preparation Methods | 11-5 |

| Table 11-4: | Analytical Methods at Laboratories Used | 11-6 |

| Table 11-5: | Analytical Methods Reported Elements and Detection Limits | 11-7 |

| Table 11-6: | Control Sample Insertion Rates | 11-11 |

| Table 12-1: | External Data Verification | 12-2 |

| Table 13-1: | Testwork Summary | 13-2 |

| Table 13-2: | Mineralogy and Deportment Assessments | 13-4 |

| Table 13-3: | Comminution Testwork | 13-6 |

| Table 13-4: | Flotation Testwork | 13-7 |

| Table 13-5: | Mill Design | 13-11 |

| Table 13-6: | Metallurgical Recovery and Concentrate Grade Forecasts | 13-13 |

| Table 14-1: | Estimation Domains, Valley Deposit | 14-9 |

| Table 14-2: | Resource Confidence Classifications, Valley Deposit | 14-13 |

| Table 14-3: | Resource Model Estimation Domains, Lornex Deposit | 14-21 |

| Table 14-4: | Resource Confidence Classifications, Lornex Deposit | 14-25 |

| Table 14-5: | Resource Model Estimation Domains, Highmont Deposit | 14-32 |

| Table 14-6: | Resource Confidence Classifications, Highmont Deposit | 14-34 |

| Table 14-7: | Resource Model Estimation Domains, Bethlehem Deposit | 14-40 |

| Table 14-8: | Resource Confidence Classifications, Bethlehem Deposit | 14-46 |

| Table 14-9: | Pit Shell Input Parameters | 14-46 |

| Table 14-10: | Mineral Resource Summary Table | 14-47 |

| Table 15-1: | Mineral Reserves Summary Table | 15-4 |

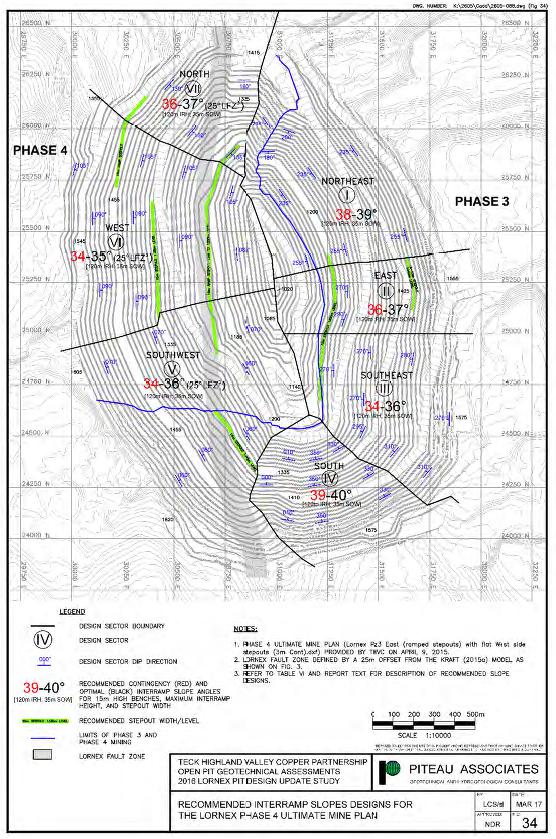

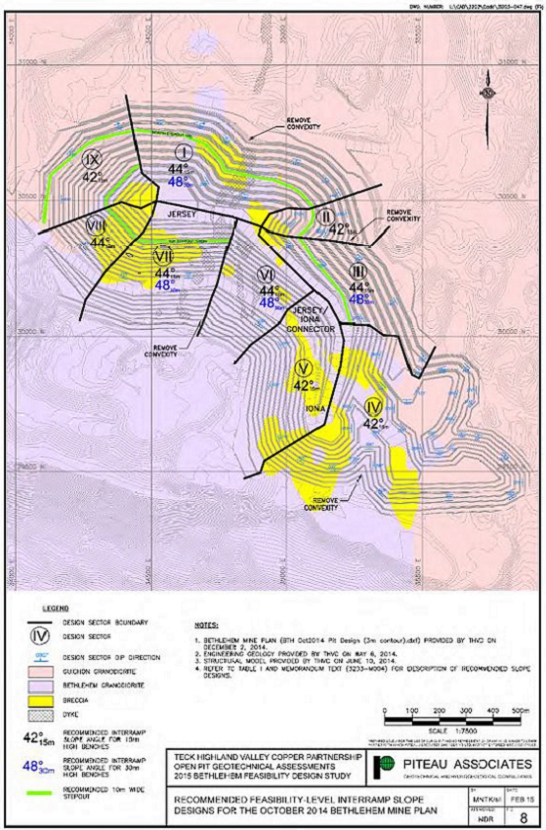

| Table 16-1: | Geotechnical Design Basis | 16-2 |

| Table 16-2: | Design Acceptability Criteria | 16-3 |

| Table 16-3: | Pit Phases | 16-11 |

| Table 16-4: | Peak Production Equipment Requirements | 16-17 |

| Table 17-1: | Mill Design Criteria | 17-7 |

| Table 17-2: | Mill Throughput by Grinding Line | 17-7 |

| Table 17-3: | Grinding Circuit | 17-9 |

| Table 17-4: | Grinding Line Process Parameters | 17-10 |

| Table 17-5: | Key Reagents and Consumables | 17-23 |

| Table 18-1: | Current TSF and Associated Features | 18-8 |

| Table 18-2: | TSF-Related Changes and Modifications Required In Support Of LOM Plan | 18-8 |

| Table 19-1: | Metal Price and Exchange Rate Forecasts | 19-6 |

| Table 20-1: | Key Permits | 20-5 |

| Table 20-2: | Additional Key Permits and Authorizations for LOM Plan | 20-6 |

| Table 21-1: | Capital Cost Estimate Summary Table (C$M, nominal terms) | 21-2 |

| Table 21-2: | Operating Cost Estimate Summary Table (C$M, nominal terms) | 21-3 |

| Table 21-3: | Unit Operating Cost Estimate Summary Table (C$/t, nominal terms) | 21-3 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

List Of Figures

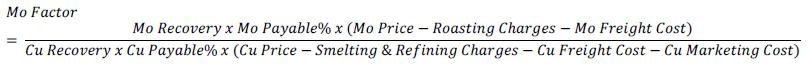

| Figure 2-1: | Project Location, Provincial | 2-2 |

| Figure 4-1: | Mineral Tenure Location Map | 4-2 |

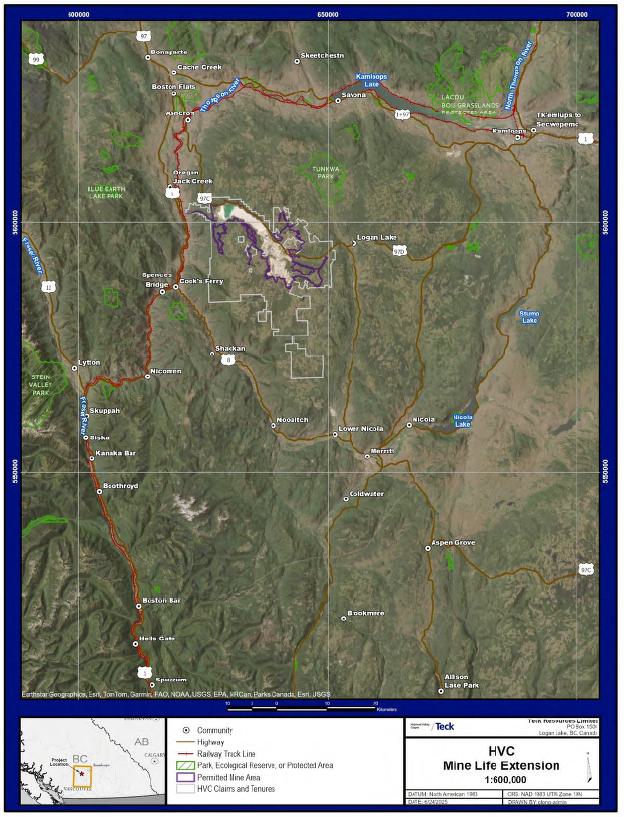

| Figure 4-2: | Surface Land Holders | 4-6 |

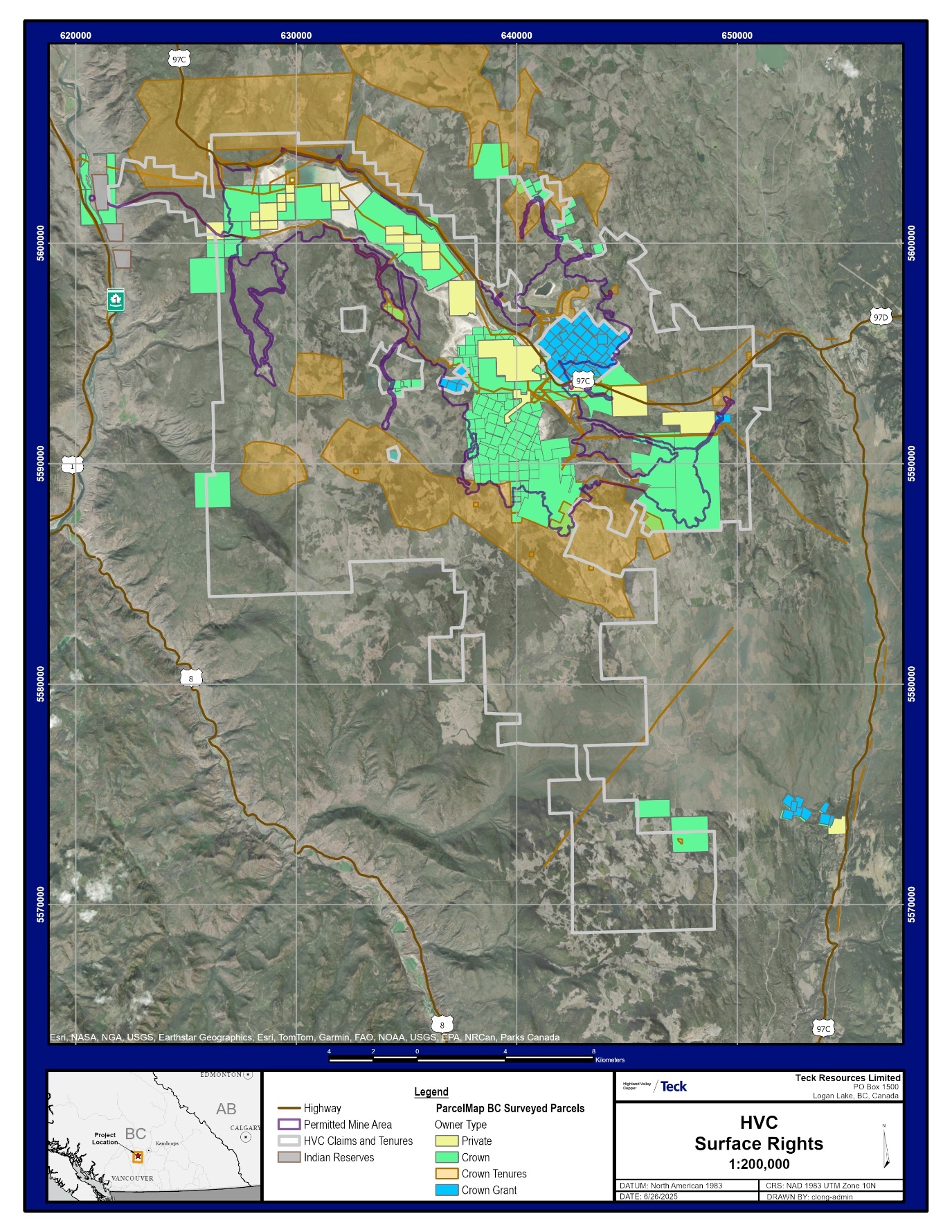

| Figure 6-1: | Location Plan, Current and Former Open Pits | 6-4 |

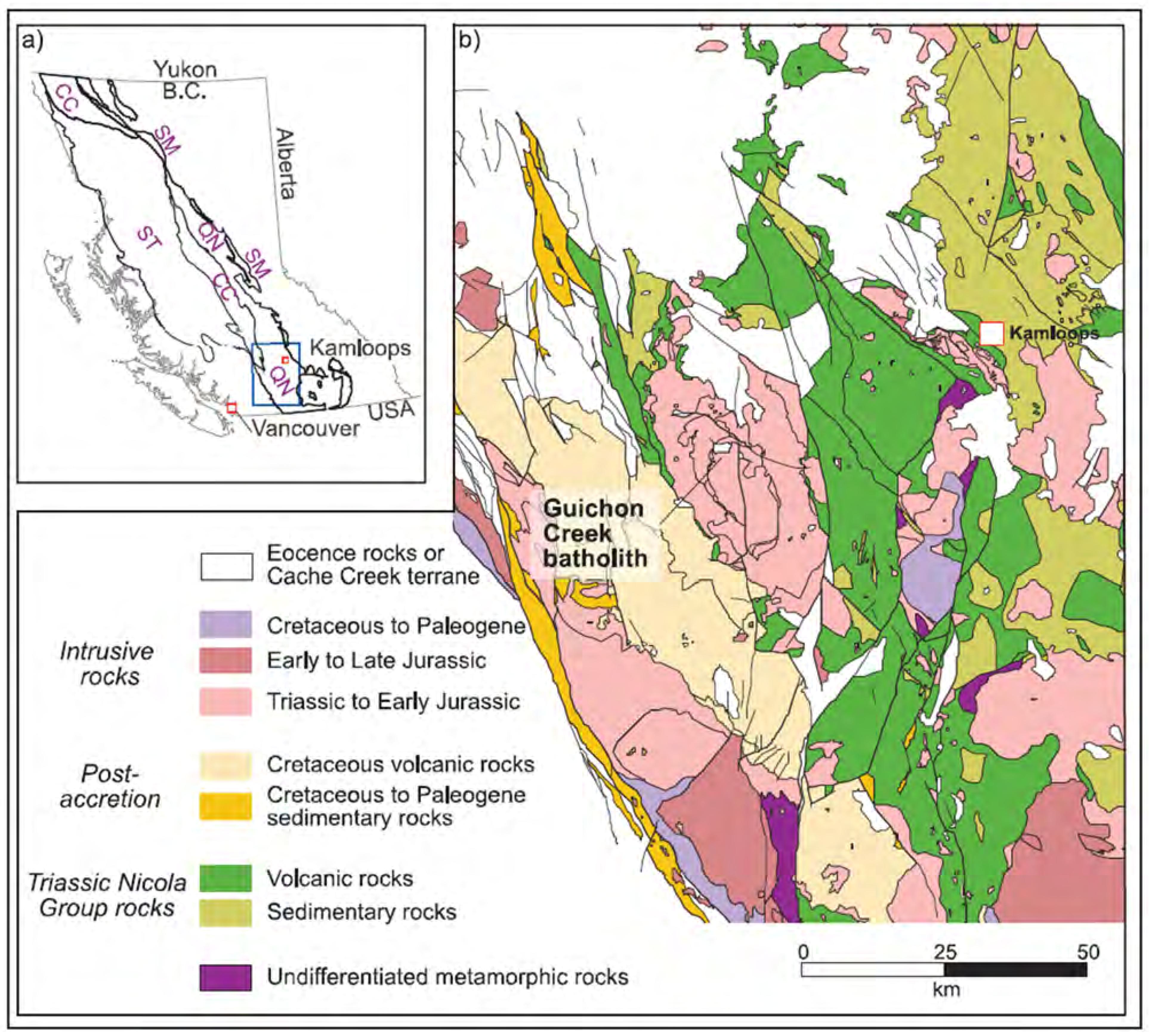

| Figure 7-1: | Regional Geology Map | 7-2 |

| Figure 7-2: | Deposit Area Geology Plan | 7-5 |

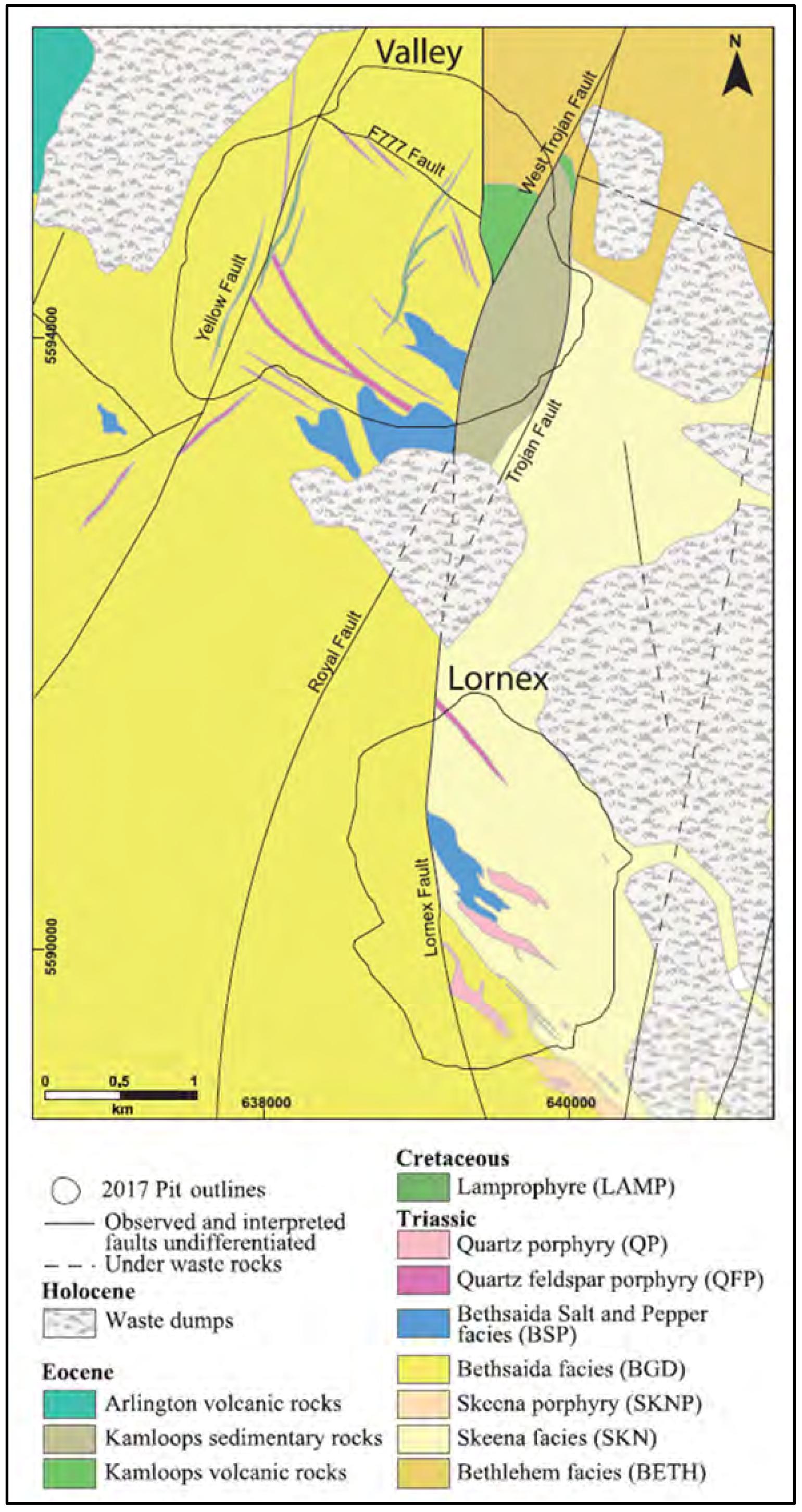

| Figure 7-3: | Geology Map, Valley–Lornex Deposit | 7-8 |

| Figure 7-4: | Cross-Section, Valley–Lornex Deposit | 7-9 |

| Figure 7-5: | Alteration and Mineralization Map, Valley–Lornex Deposit | 7-12 |

| Figure 7-6: | Cross-Section, Lornex Deposit | 7-15 |

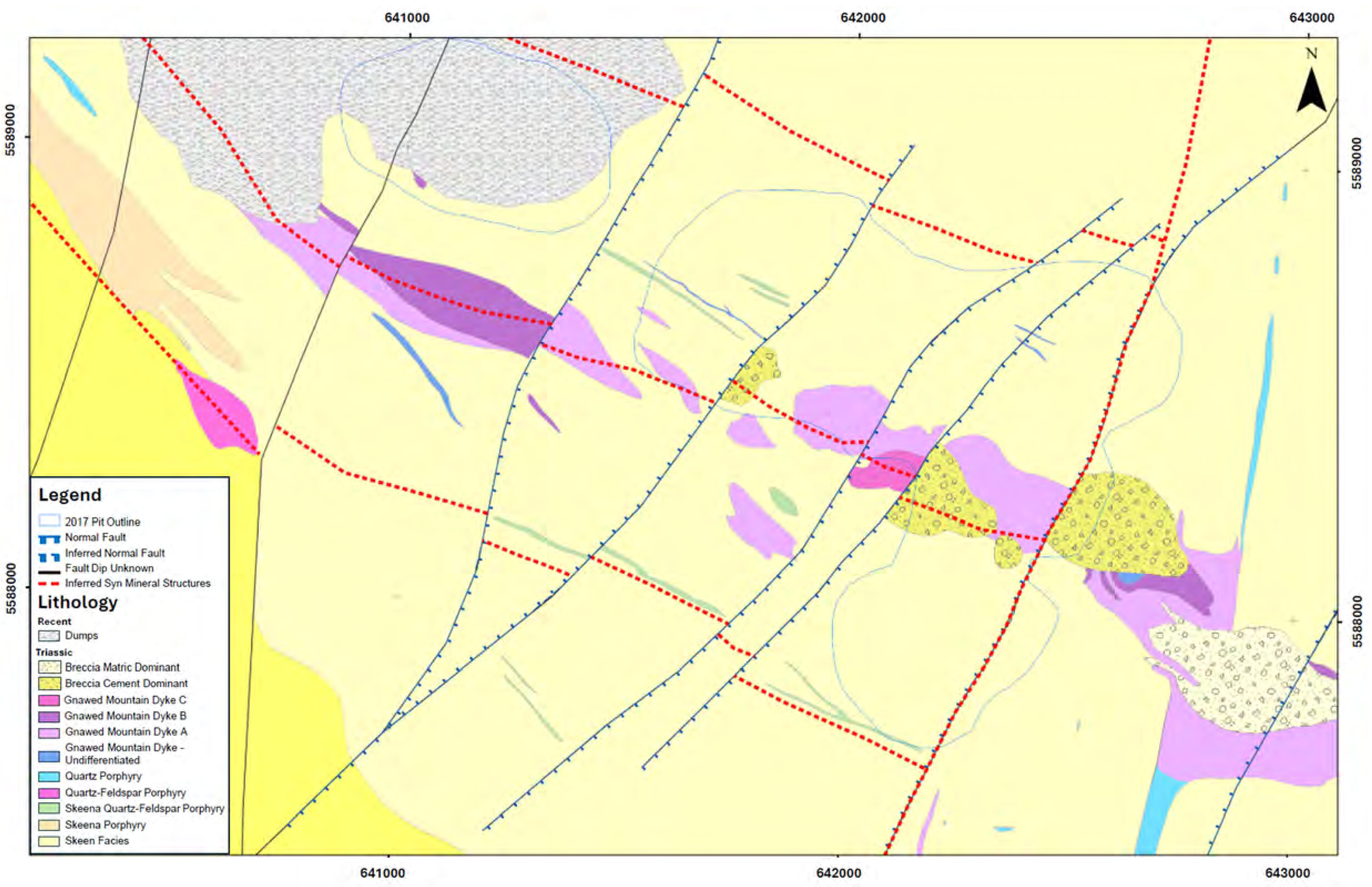

| Figure 7-7: | Geology Map, Highmont Deposit | 7-19 |

| Figure 7-8: | Mineralization Map Showing Major Structures, Highmont Deposit | 7-20 |

| Figure 7-9: | Overprinting Alteration Plan, Highmont Deposit | 7-22 |

| Figure 7-10: | High Temperature Alteration Plan, Highmont Deposit | 7-23 |

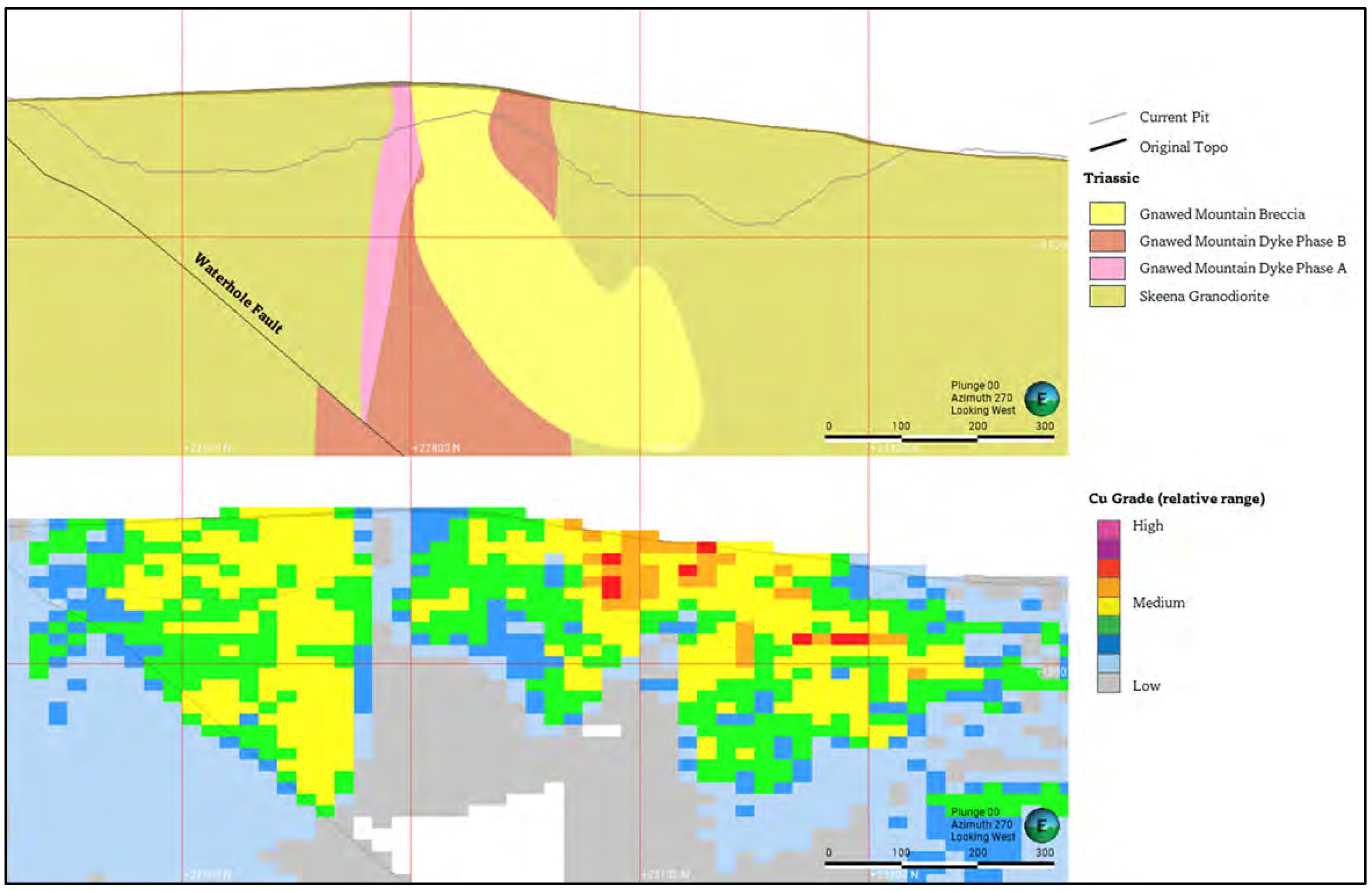

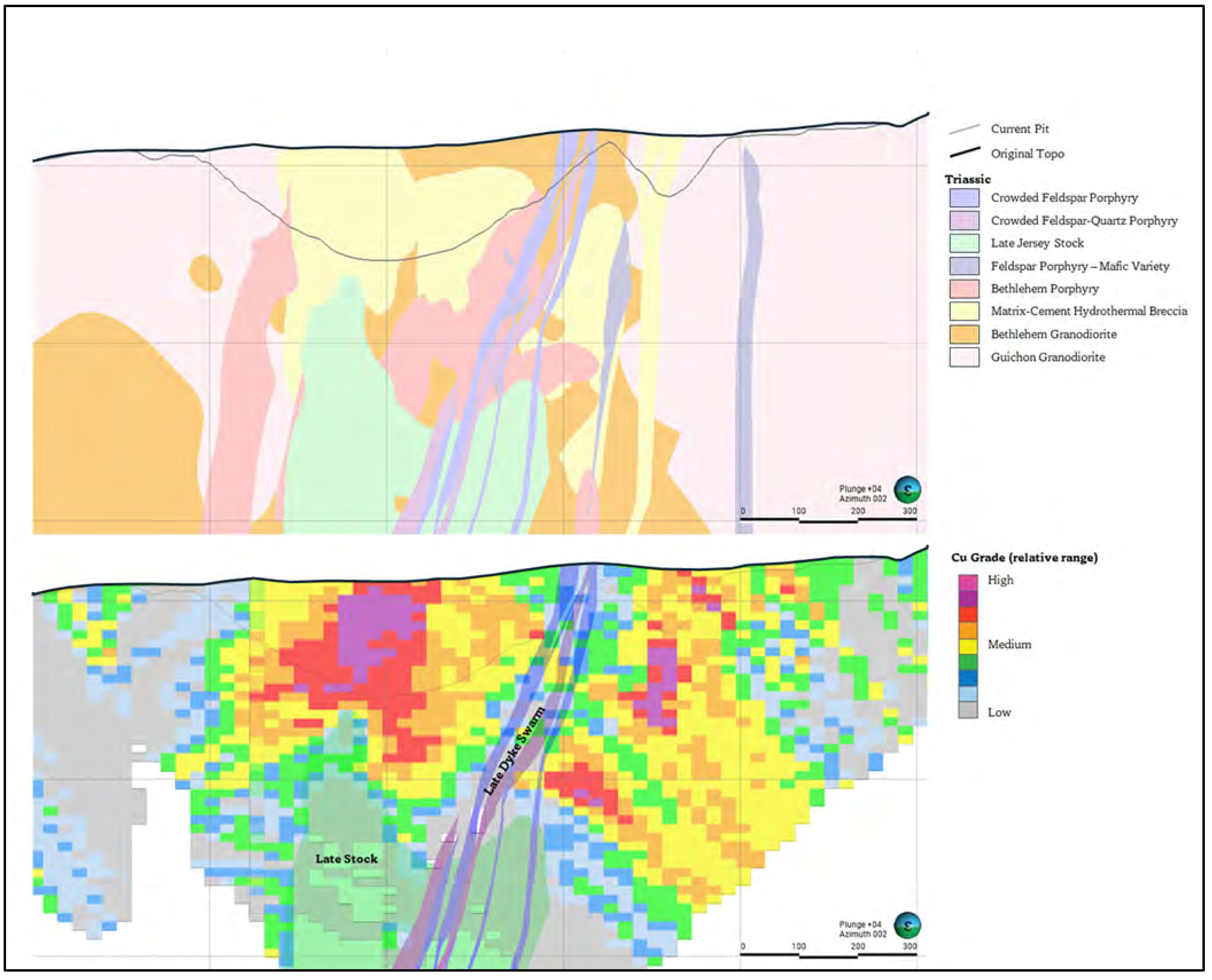

| Figure 7-11: | Lithology and Mineralization Sections, Highmont Deposit | 7-25 |

| Figure 7-12: | Lithology, Alteration, and Mineralization Map, Bethlehem Deposit | 7-27 |

| Figure 7-13: | Geological Cross-Section, Bethlehem Deposit | 7-28 |

| Figure 8-1: | Schematic Section, Porphyry Copper Deposit | 8-3 |

| Figure 8-2: | Schematic Section Showing Typical Alteration Assemblages | 8-4 |

| Figure 9-1: | Geochemical Sample Location Map | 9-3 |

| Figure 10-1: | Project Drill Collar Location Plan | 10-6 |

| Figure 10-2: | Drilling Used In Mineral Resource Estimation, Valley Deposit | 10-7 |

| Figure 10-3: | Drilling Used In Mineral Resource Estimation, Lornex Deposit | 10-8 |

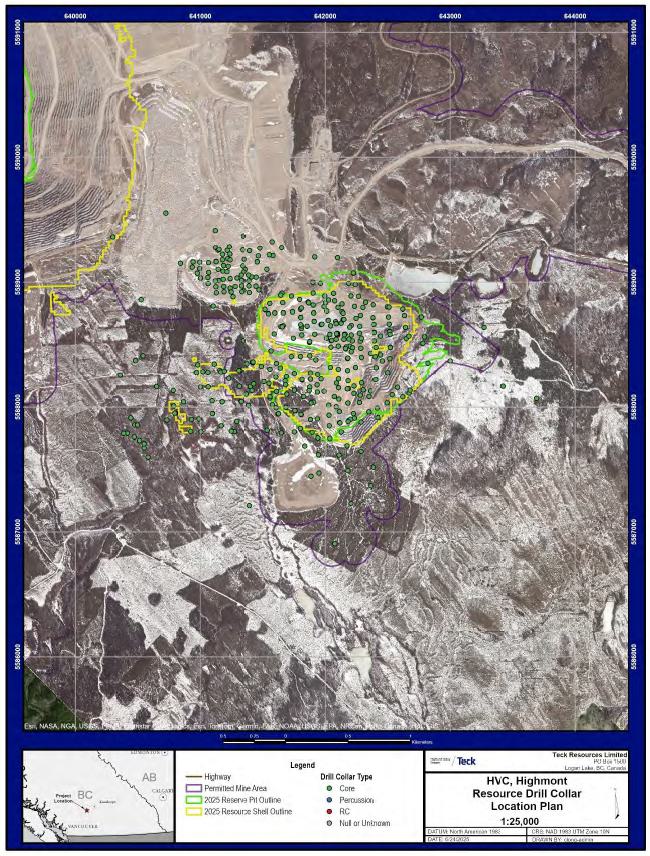

| Figure 10-4: | Drilling Used In Mineral Resource Estimation, Highmont Deposit | 10-9 |

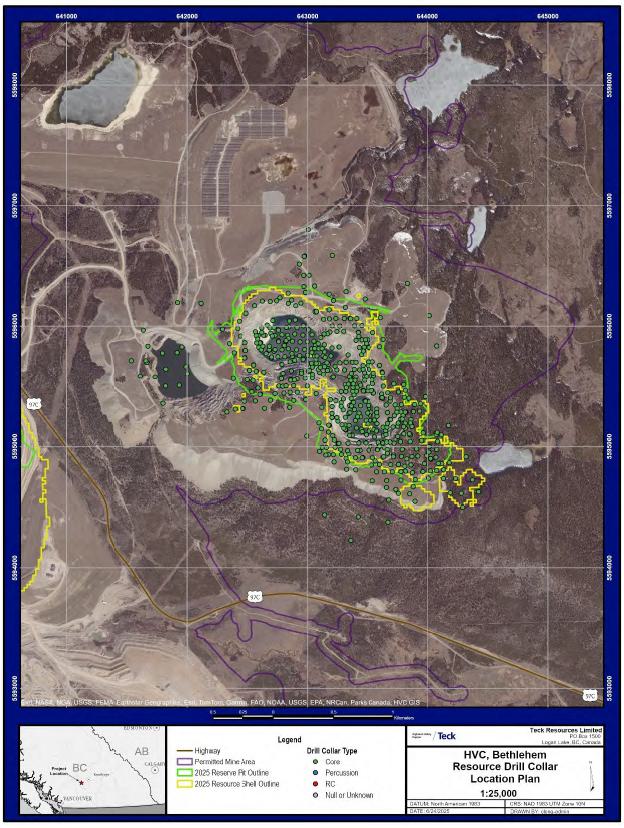

| Figure 10-5: | Drilling Used In Mineral Resource Estimation, Bethlehem Deposit | 10-10 |

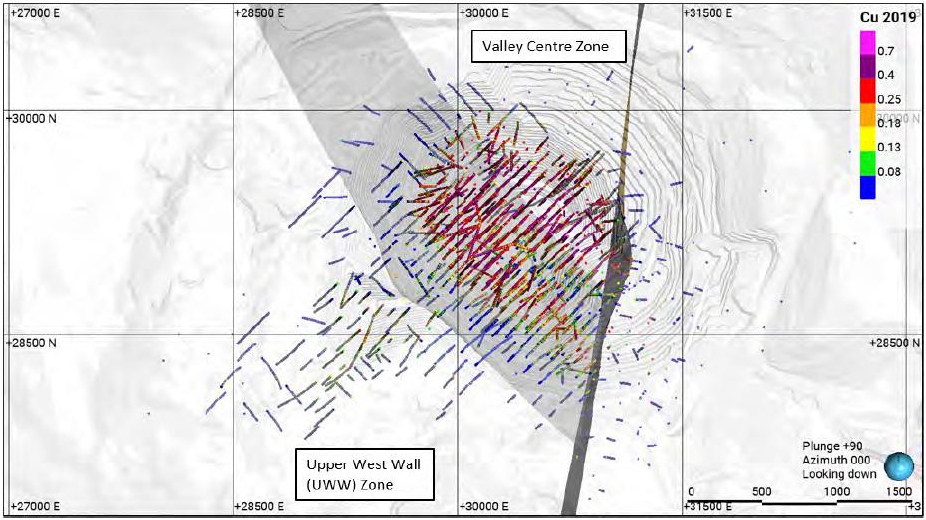

| Figure 14-1: | Plan View, Drilling Showing Copper Assay Results, Valley Deposit | 14-2 |

| Figure 14-2: | Plan View, Drilling Showing Molybdenum Assay Results, Valley Deposit | 14-3 |

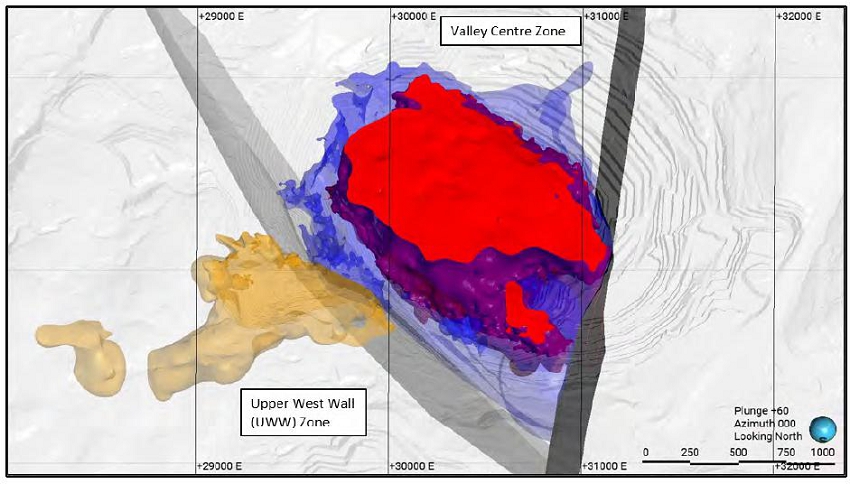

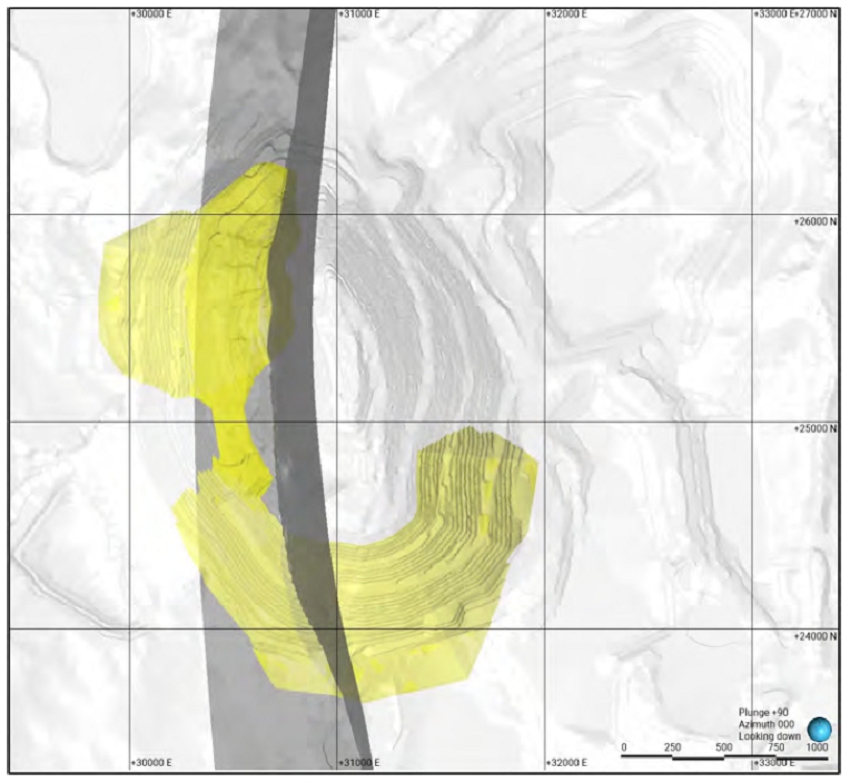

| Figure 14-3: | Copper Grade Shell, Valley Deposit | 14-5 |

| Figure 14-4: | Molybdenum Grade Shell, Valley Deposit | 14-6 |

| Figure 14-5: | Copper Estimation Domains, Valley Deposit | 14-10 |

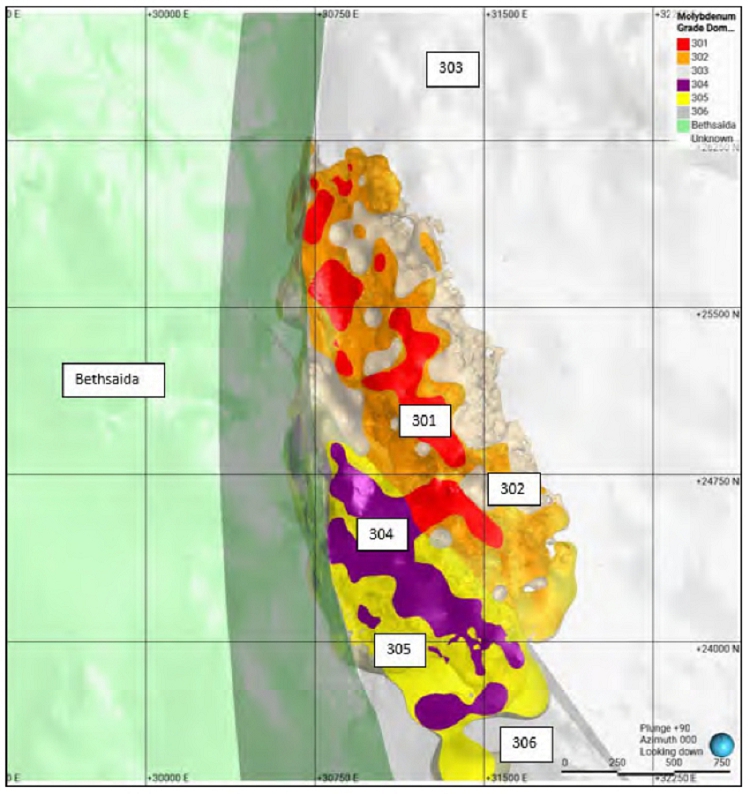

| Figure 14-6: | Molybdenum Estimation Domains, Valley Deposit | 14-11 |

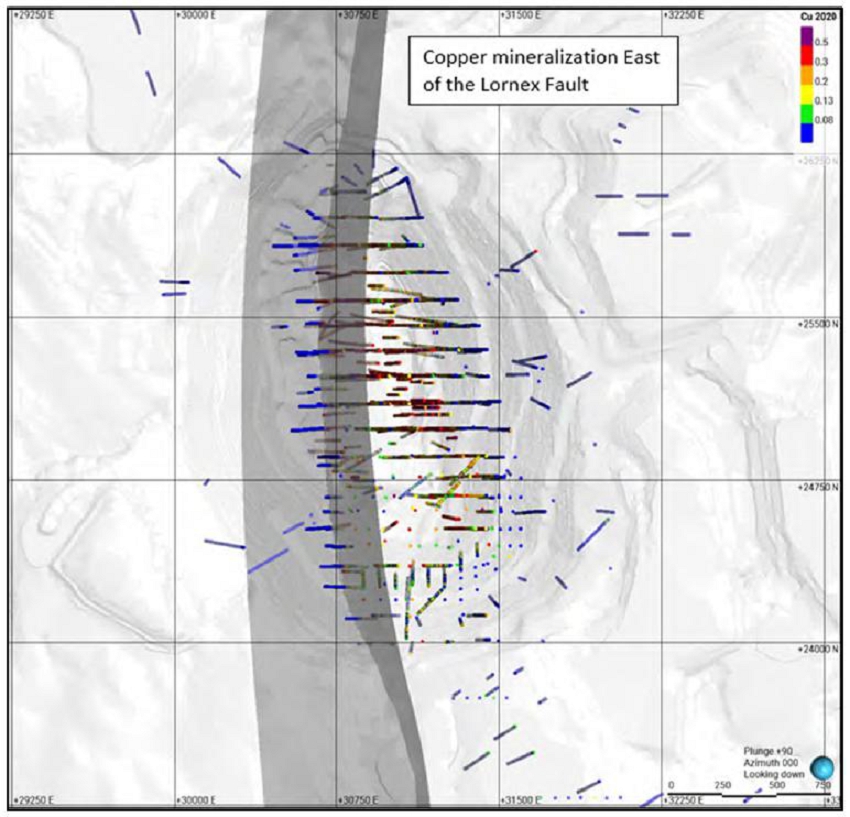

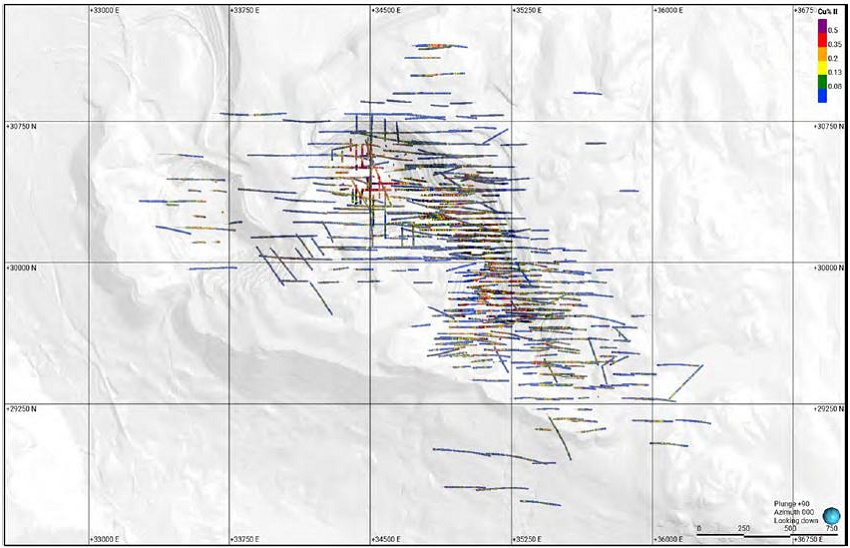

| Figure 14-7: | Plan View, Drilling Showing Copper Assay Results, Lornex Deposit | 14-15 |

| Figure 14-8: | Plan View, Drilling Showing Molybdenum Assay Results, Lornex Deposit | 14-16 |

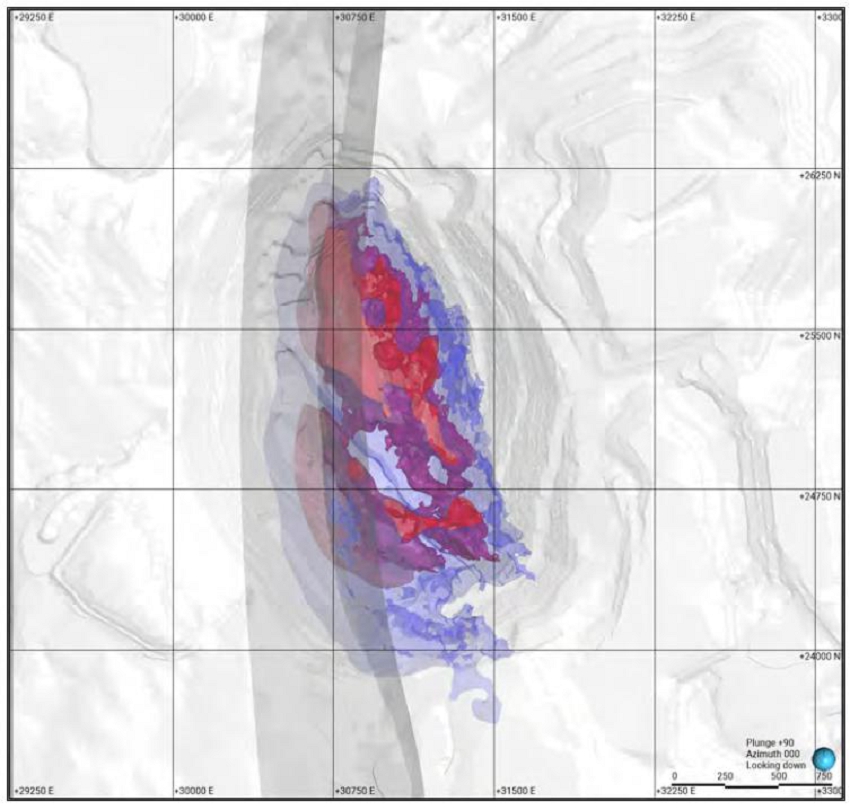

| Figure 14-9: | Copper Grade Shells, Lornex Deposit | 14-17 |

| Figure 14-10: | Molybdenum Grade Shells, Lornex Deposit | 14-18 |

| Figure 14-11: | Deformation Density Downgrade, Lornex Deposit | 14-20 |

| Figure 14-12: | Copper Estimation Domains, Lornex Deposit | 14-22 |

| Figure 14-13: | Molybdenum Estimation Domains, Lornex Deposit | 14-23 |

| Figure 14-14: | Plan View, Drilling Showing Copper Assay Results, Highmont Deposit | 14-26 |

| Figure 14-15: | Plan View, Drilling Showing Molybdenum Assay Results, Highmont Deposit | 14-27 |

| Figure 14-16: | Copper Grade Shell, Highmont Deposit | 14-28 |

| Figure 14-17: | Molybdenum Grade Shell, Highmont Deposit | 14-29 |

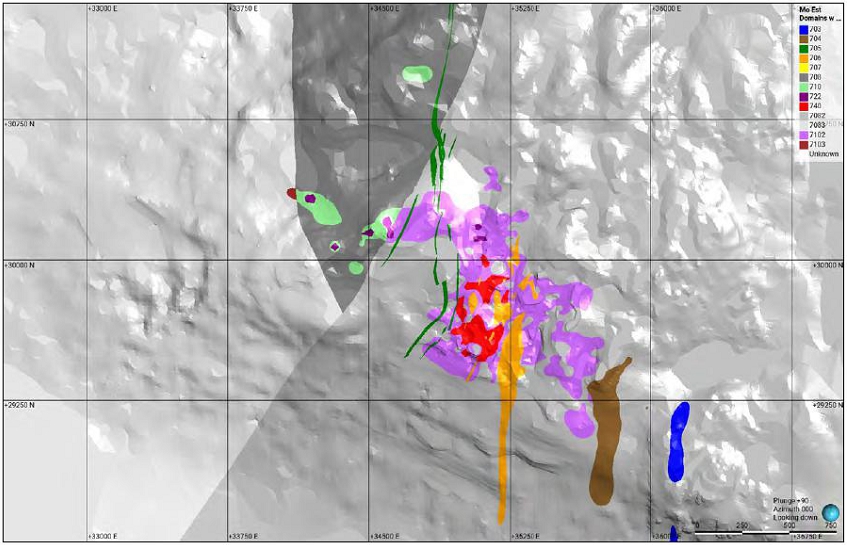

| Figure 14-18: | Copper Estimation Domains, Highmont Deposit | 14-33 |

| Figure 14-19: | Molybdenum Estimation Domains, Highmont Deposit | 14-34 |

| Figure 14-20: | Plan View, Drilling Showing Copper Assay Results, Bethlehem Deposit | 14-37 |

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| Figure 14-21 | Plan View, Drilling Showing Molybdenum Assay Results, Bethlehem Deposit | 14-38 |

| Figure 14-22: | Copper Estimation Domains, Bethlehem Deposit | 14-41 |

| Figure 14-23: | Molybdenum Estimation Domains, Bethlehem Deposit | 14-42 |

| Figure 16-1: | Valley Mine Plan, Pushback 1 | 16-4 |

| Figure 16-2: | Valley Mine Plan, Pushback 2 | 16-5 |

| Figure 16-3: | Lornex Mine Plan | 16-6 |

| Figure 16-4: | Highmont Mine Plan, Expansion | 16-7 |

| Figure 16-5: | Bethlehem Mine Plan | 16-8 |

| Figure 16-6: | WRSF Location Plan | 16-13 |

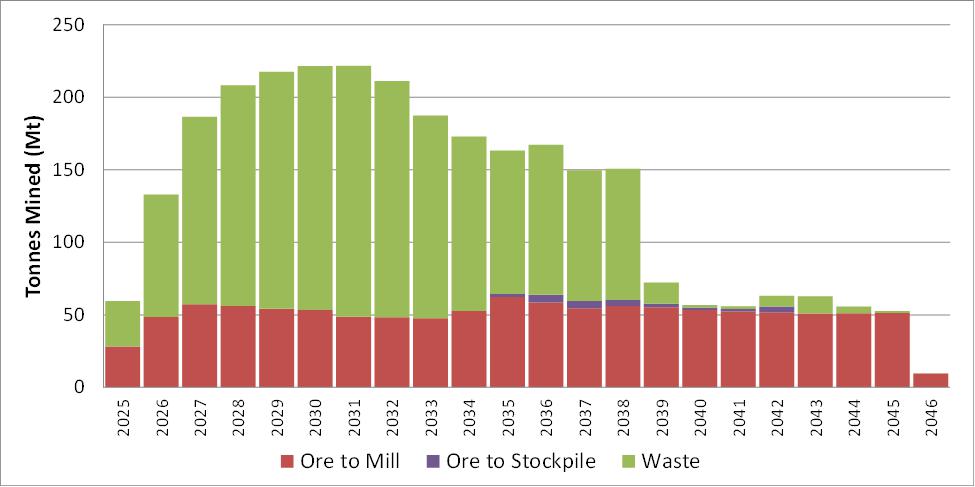

| Figure 16-7: | LOM Production Plan by Destination | 16-15 |

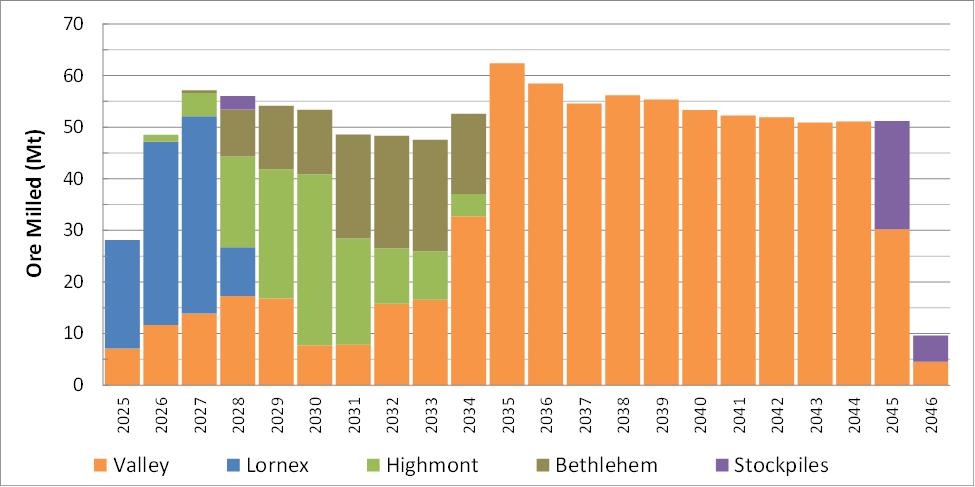

| Figure 16-8: | LOM Mill Feed by Source | 16-15 |

| Figure 17-1: | Current Conveyor Flow Sheet | 17-2 |

| Figure 17-2: | Current Crushing and Grinding Circuit | 17-3 |

| Figure 17-3: | Current Bulk Flotation Circuit | 17-4 |

| Figure 17-4: | Modifications Required for LOM Plan | 17-5 |

| Figure 17-5: | Process Flow Sheet with Modifications Required for LOM Plan | 17-6 |

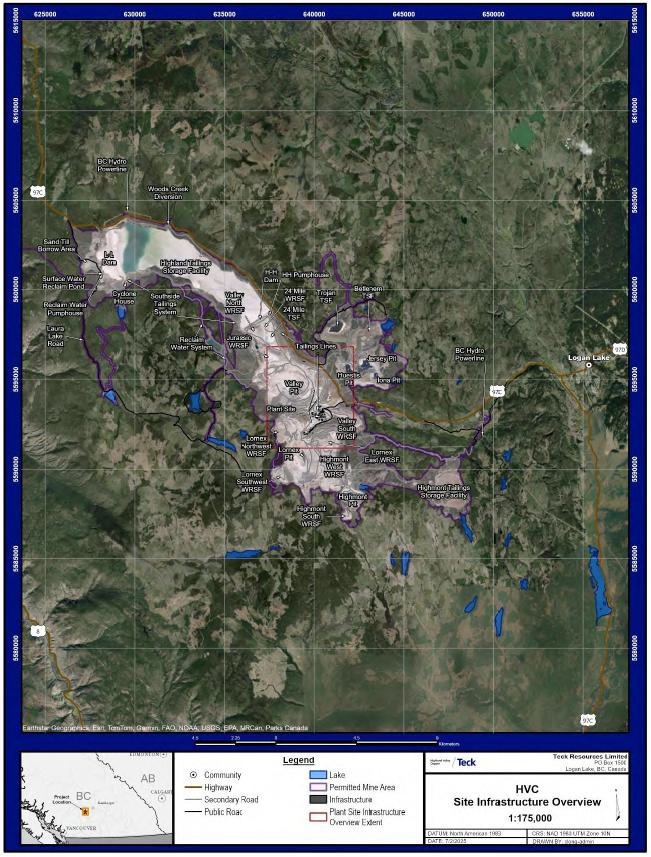

| Figure 18-1: | Current Infrastructure Location Plan, Site Overview | 18-3 |

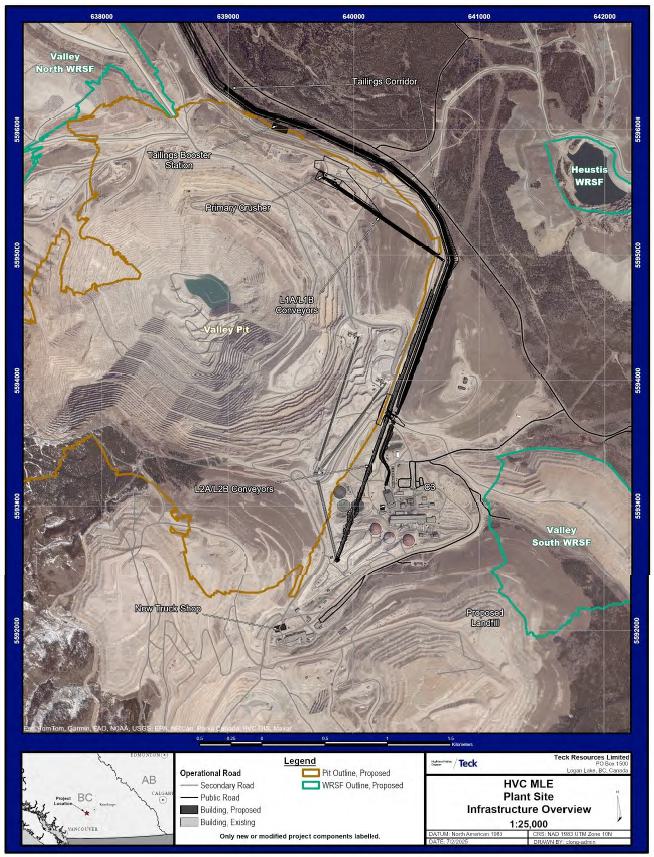

| Figure 18-2: | Current Infrastructure Location Plan, Mill Area Detail | 18-4 |

| Figure 19-1: | Copper Mine Production and Demand (kt) | 19-3 |

| Figure 19-2: | Global Demand Growth of Molybdenum by Industry | 19-4 |

Appendix A

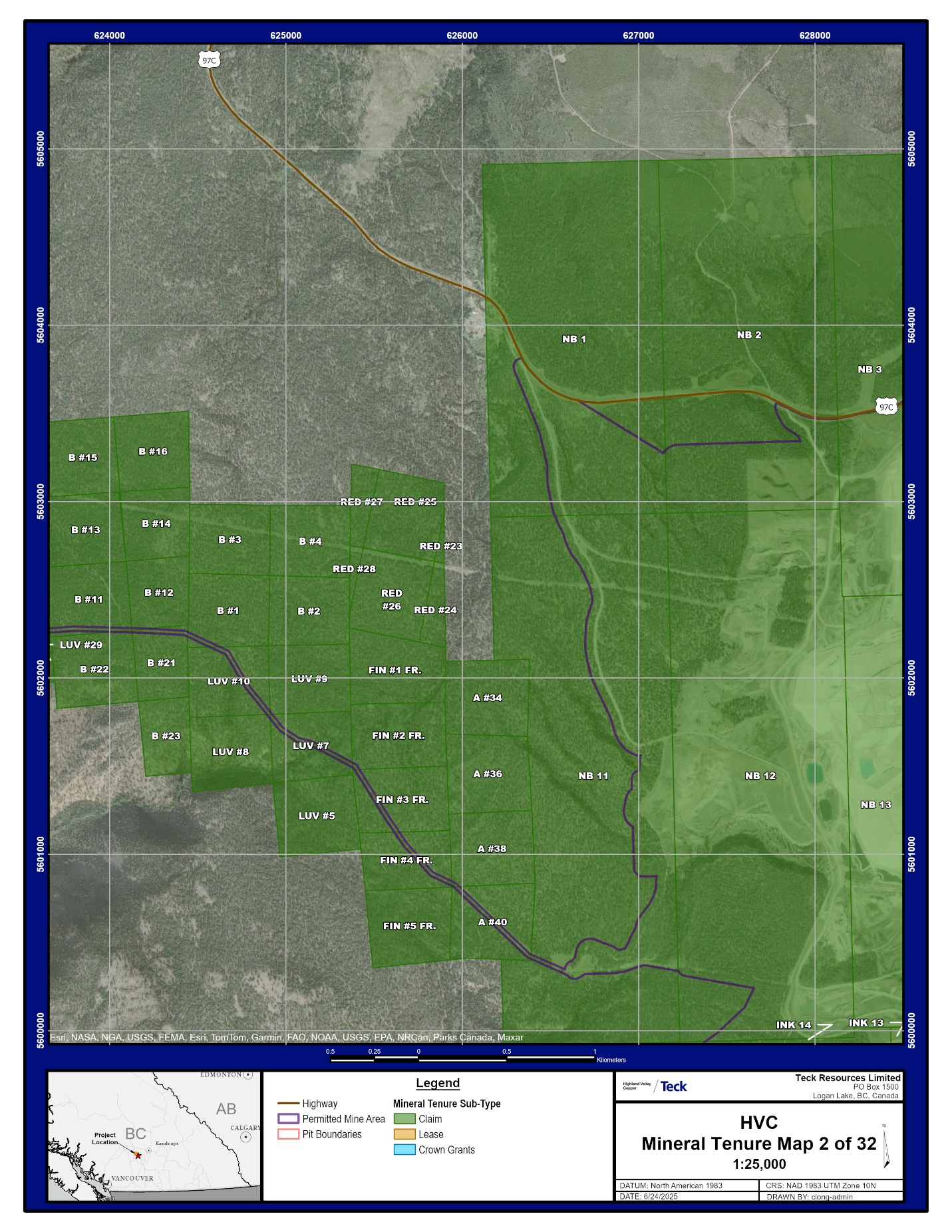

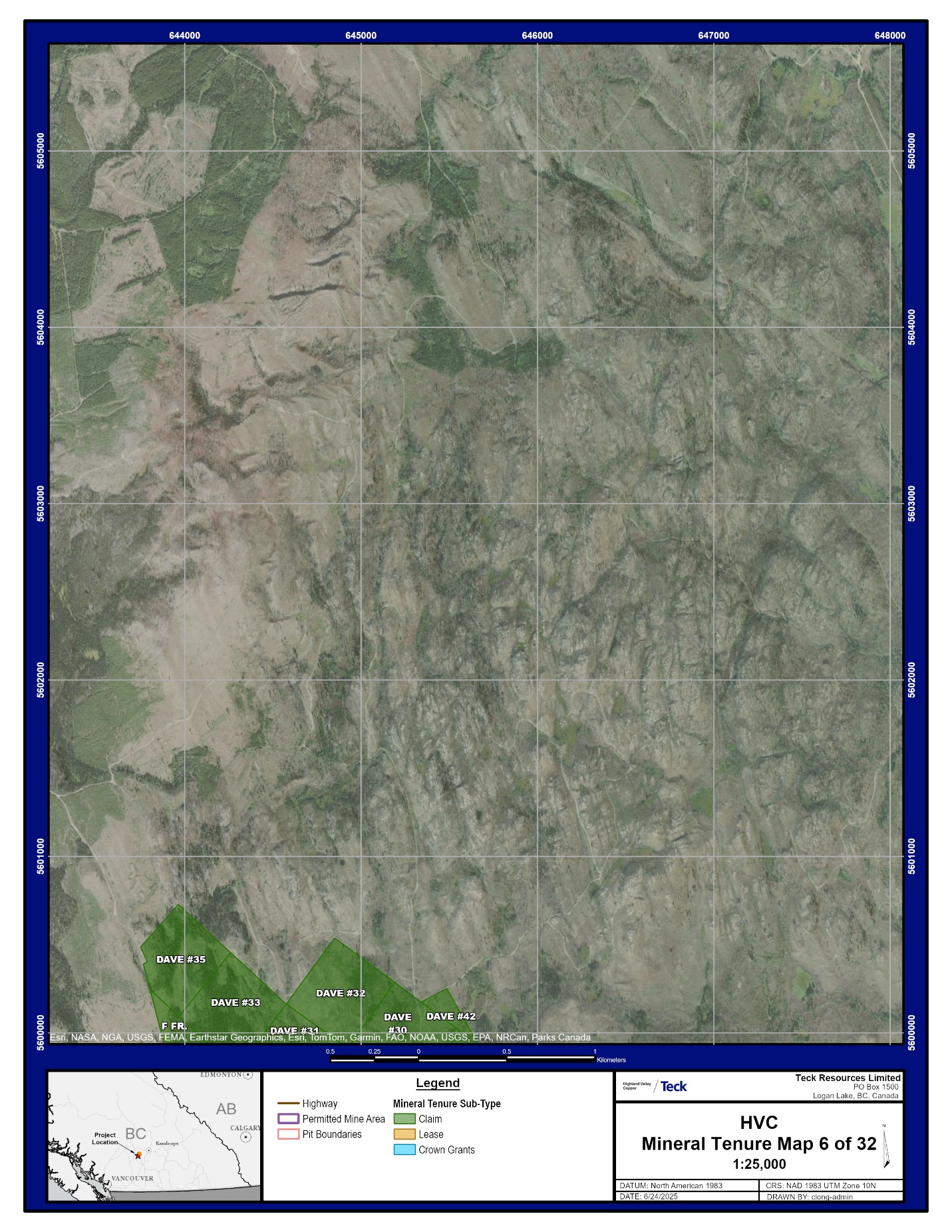

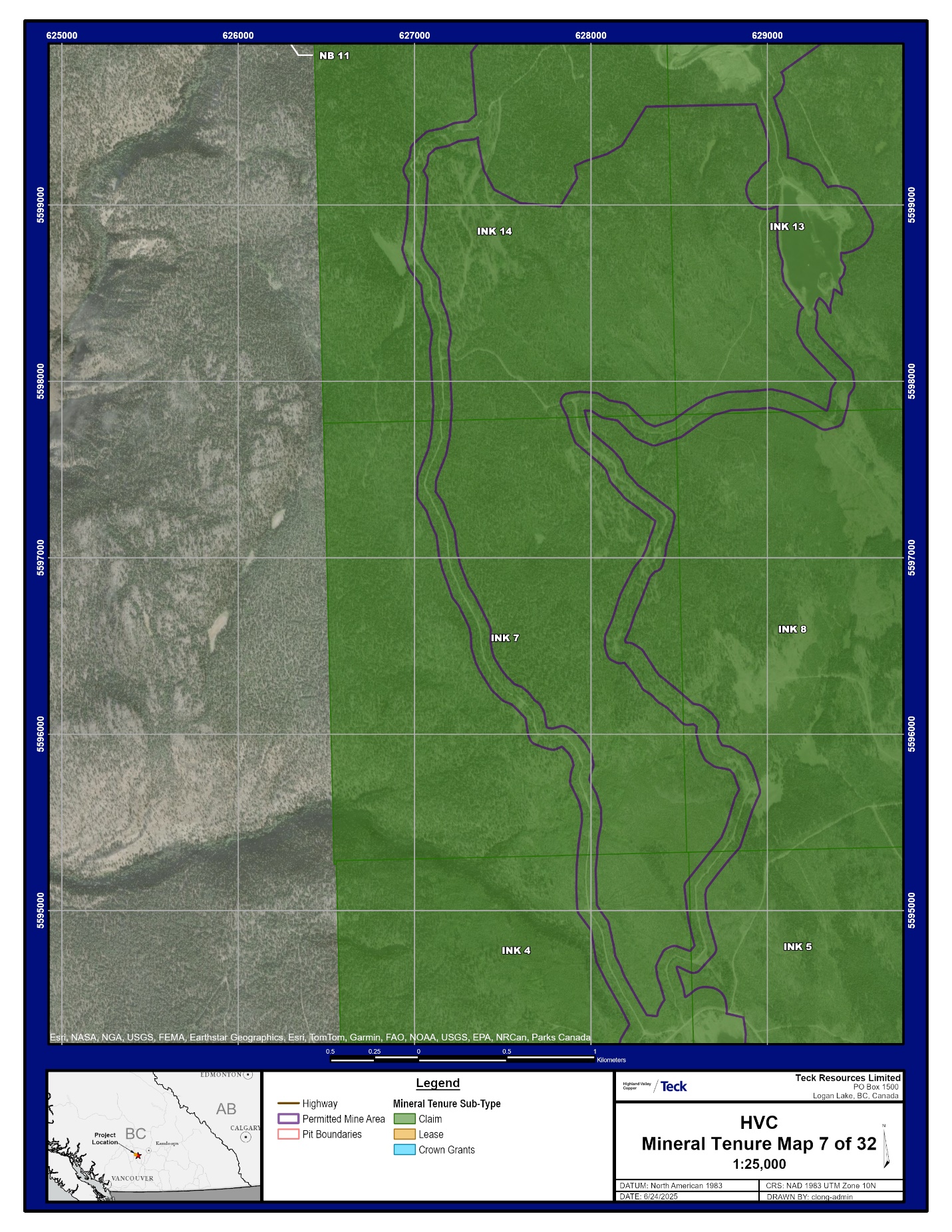

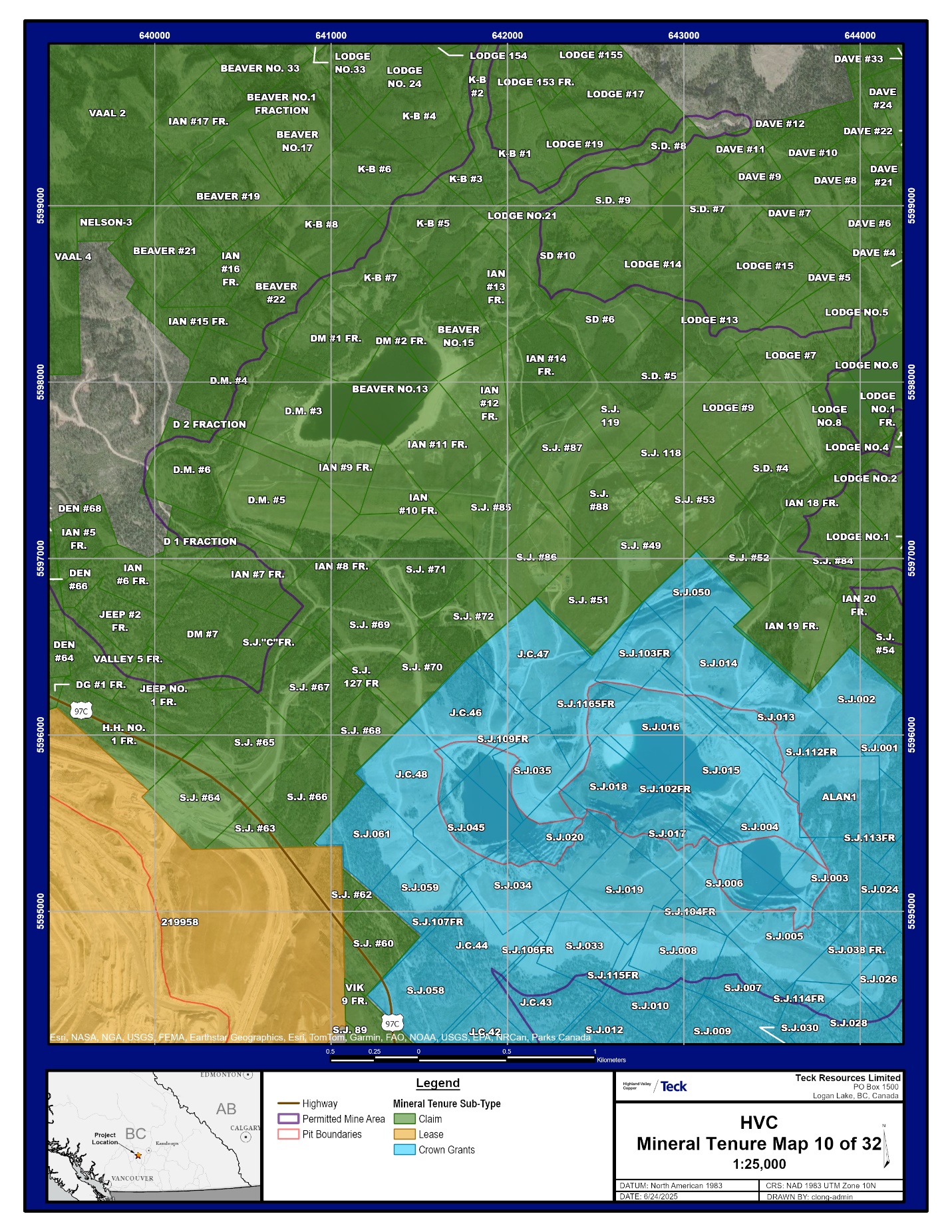

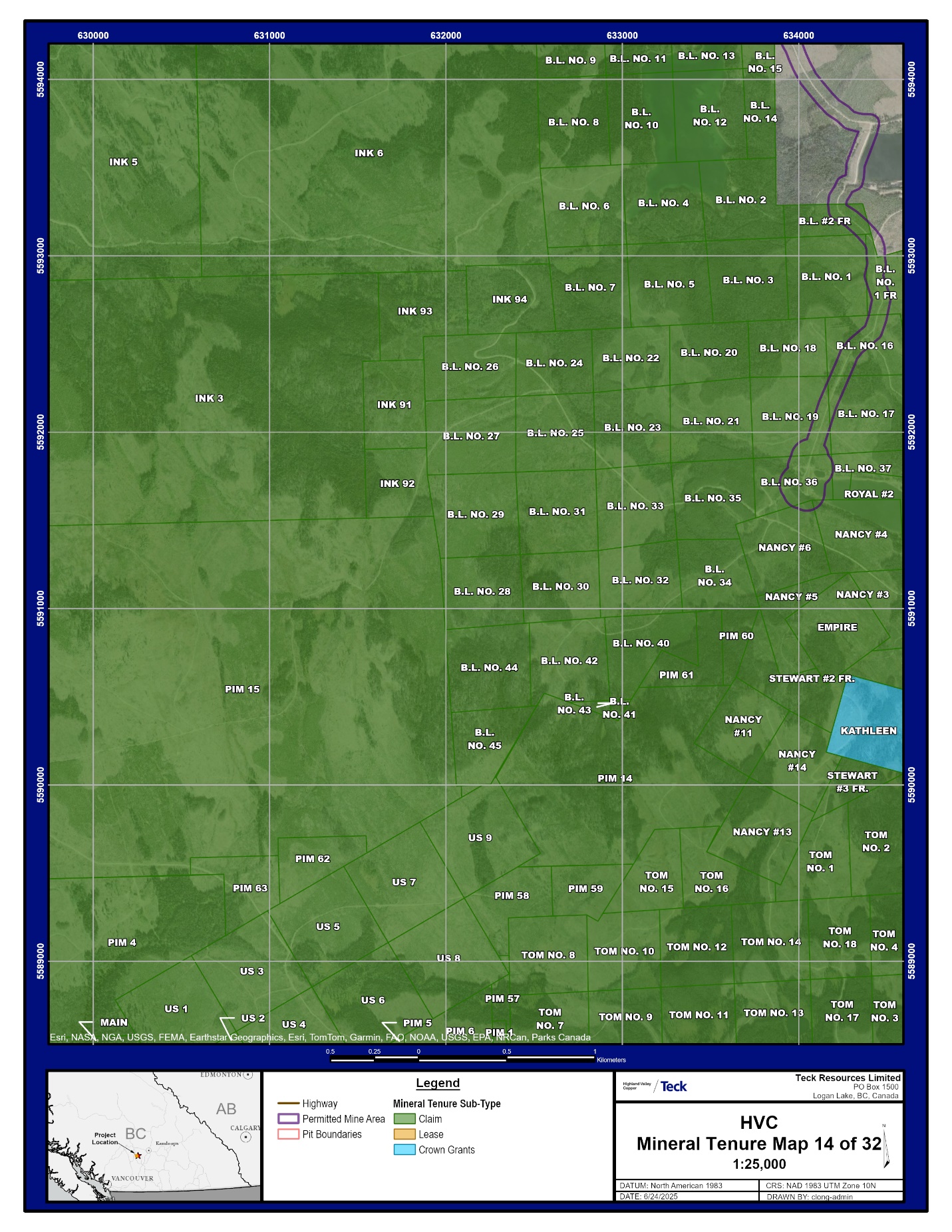

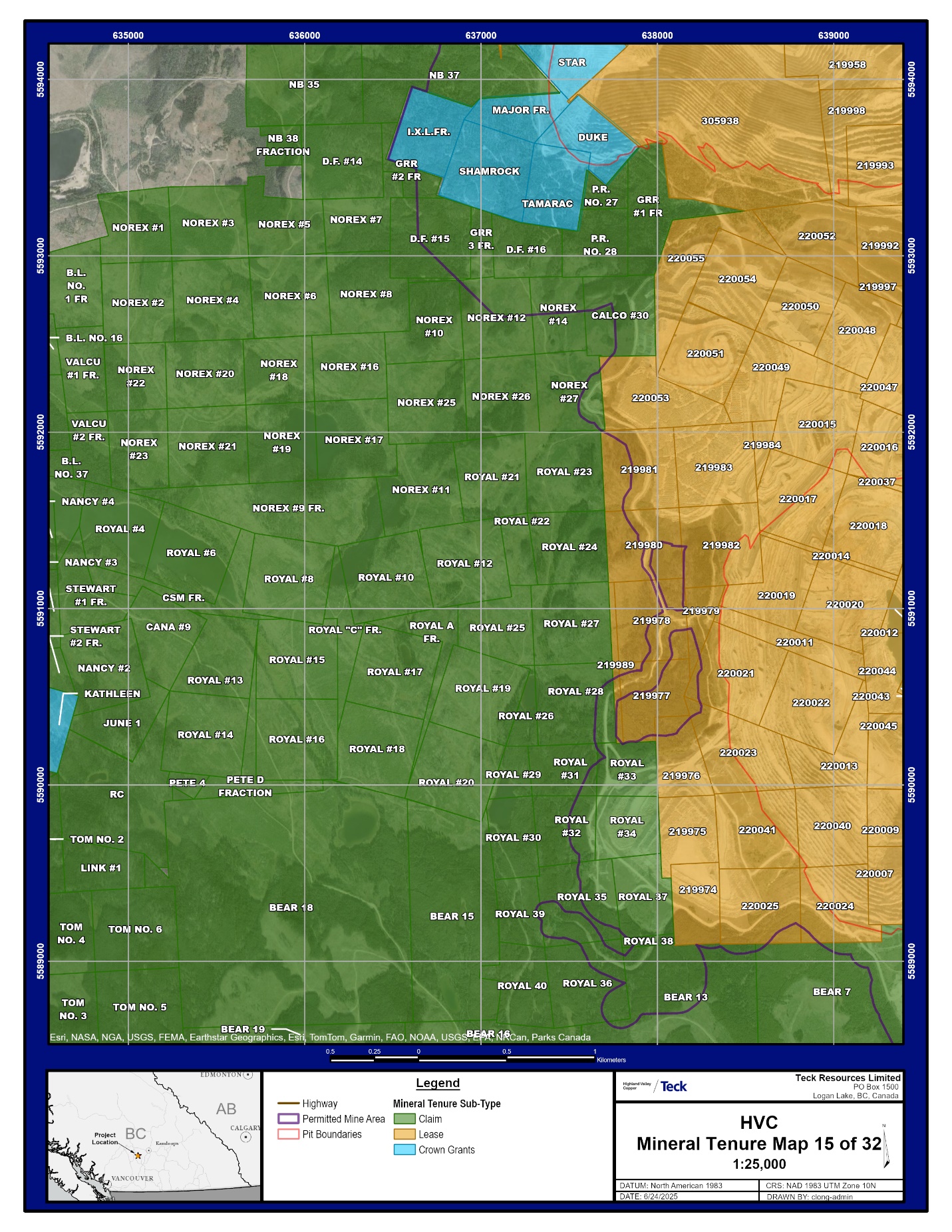

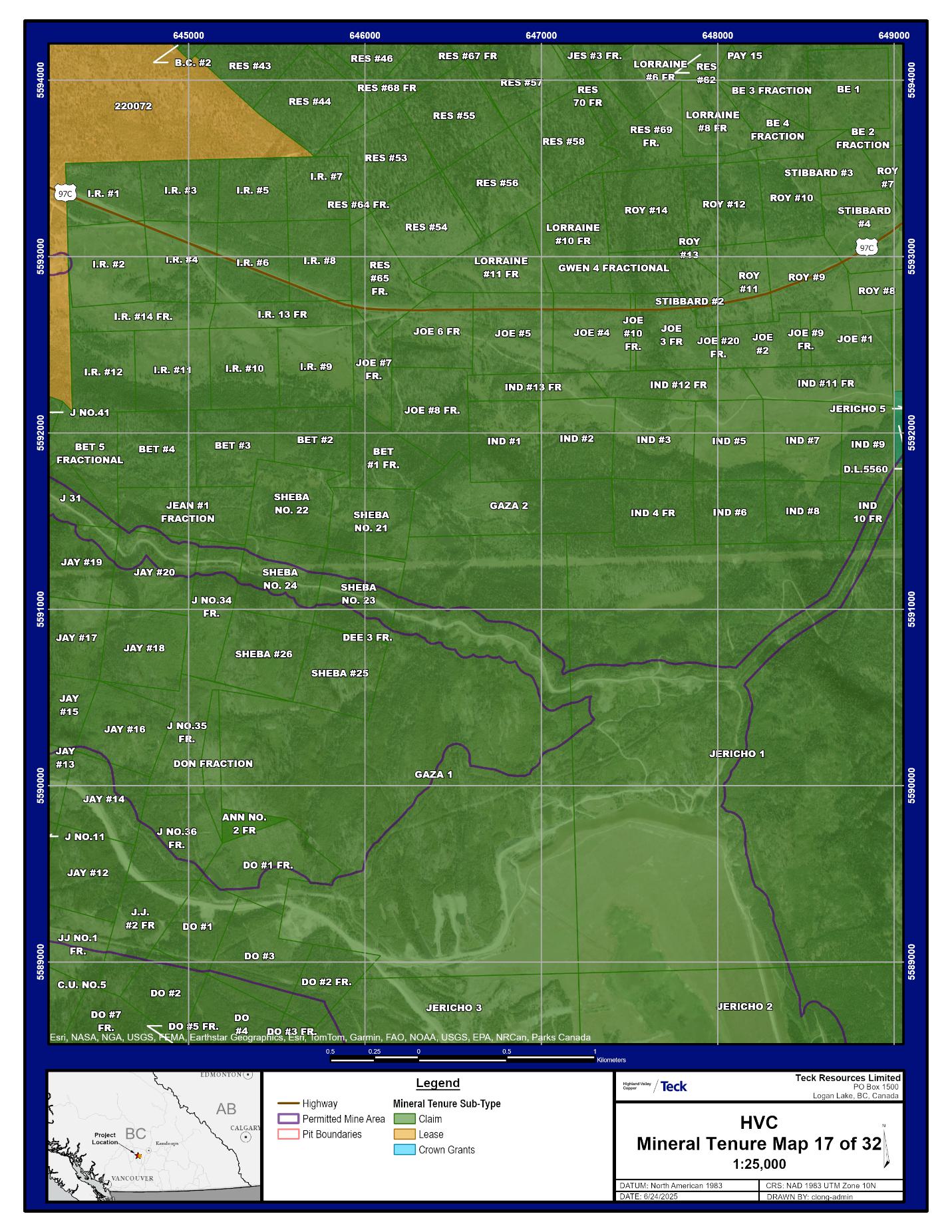

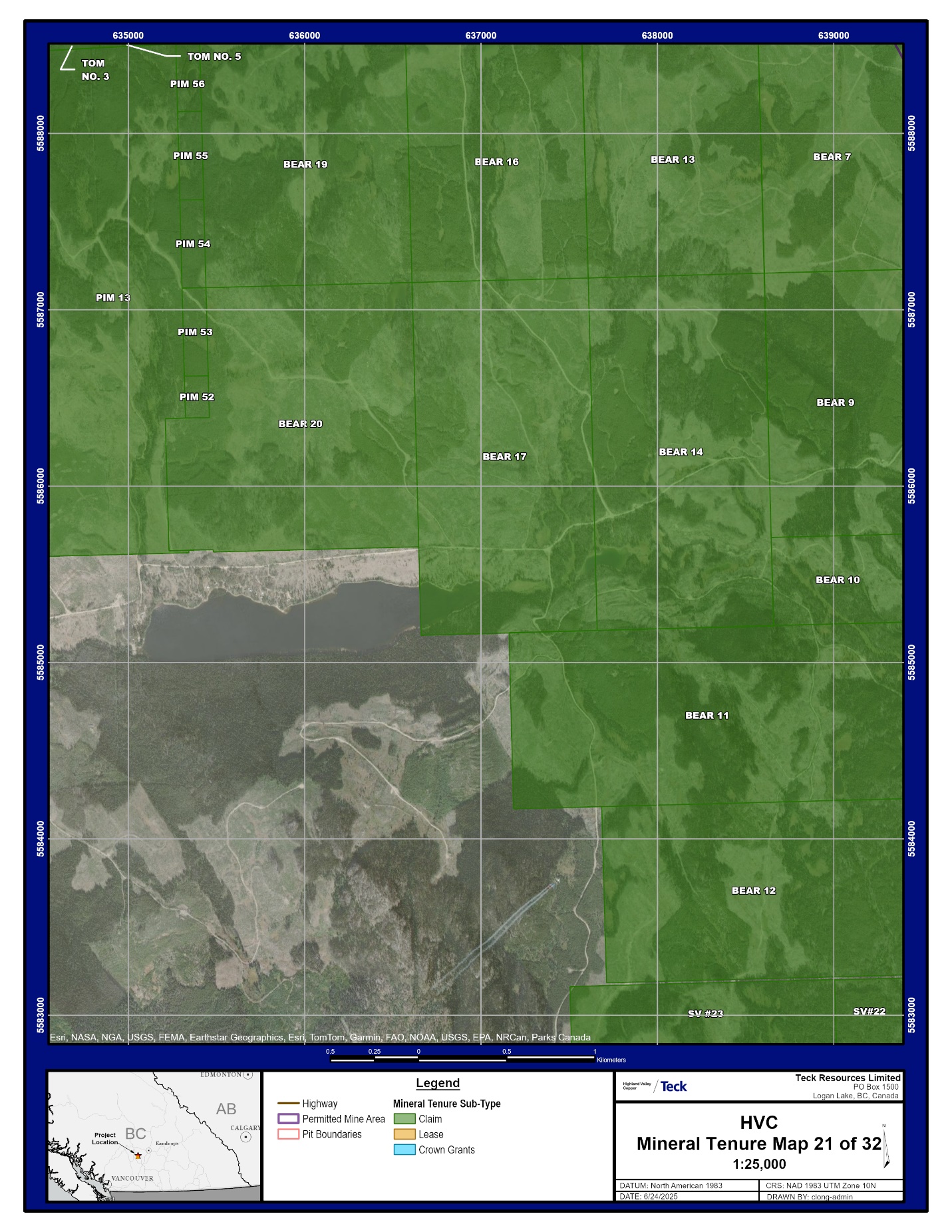

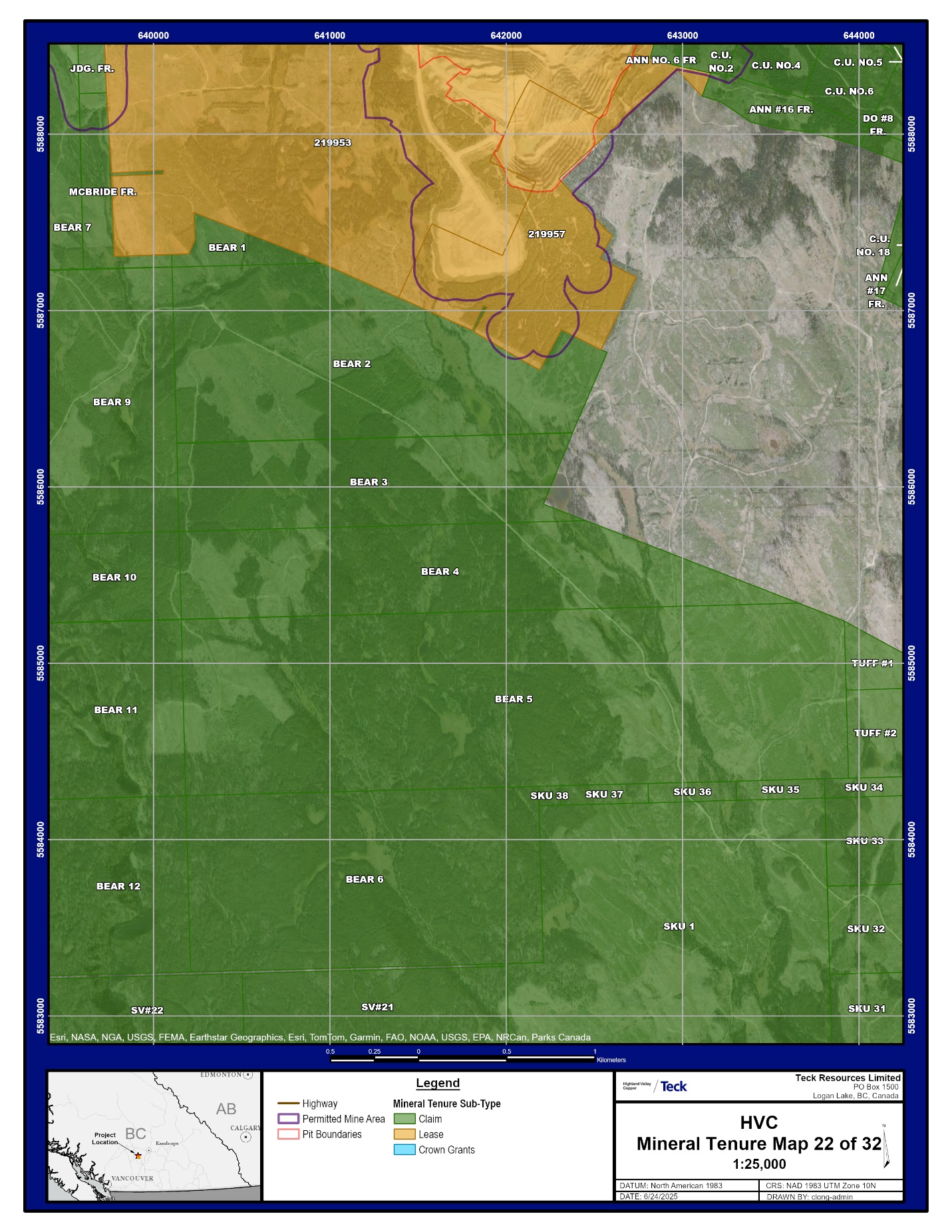

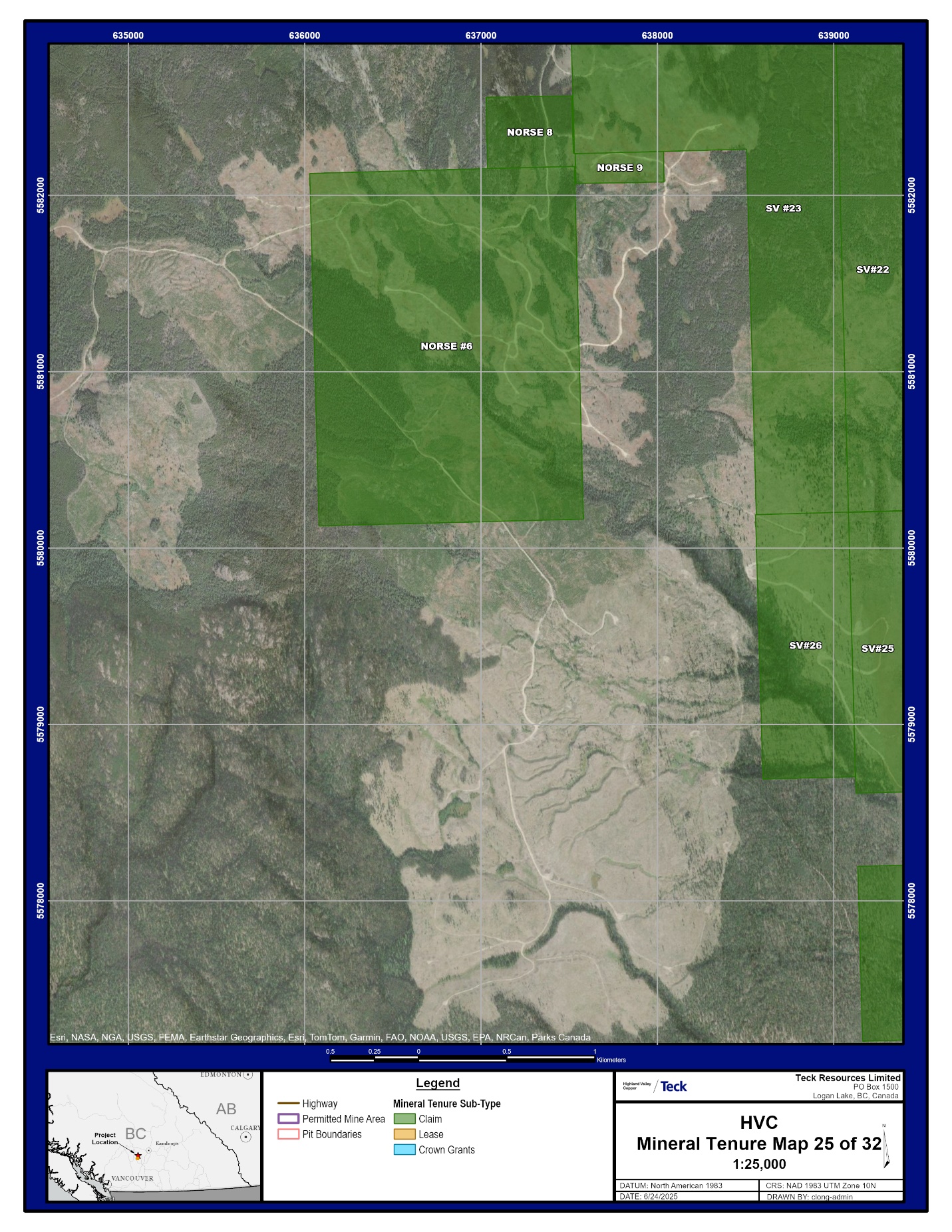

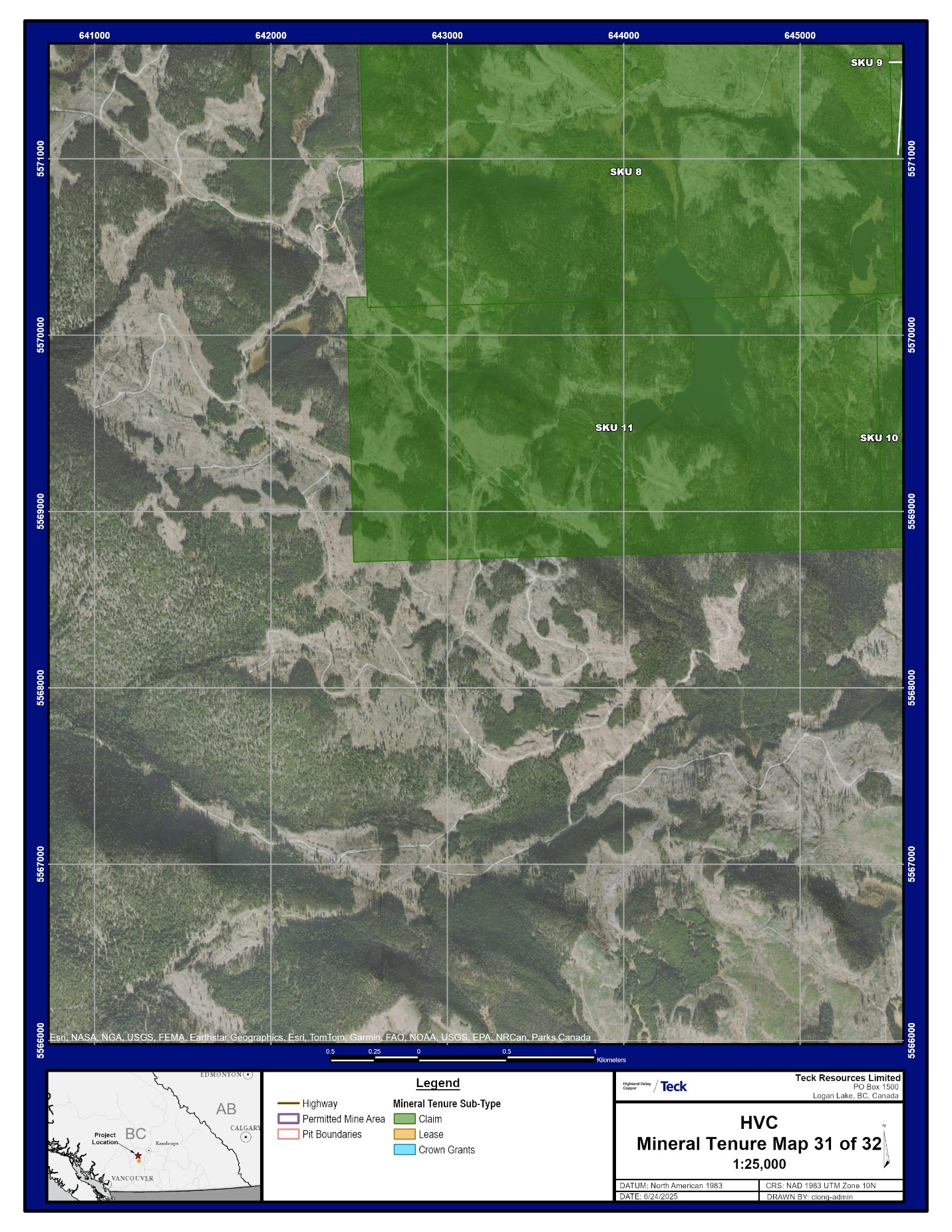

Appendix A: Detailed Mineral Tenure Table and Mineral Tenure Location Maps

| October 2025 | TOC |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| 1 | SUMMARY |

| 1.1 | Introduction |

Mr. Christopher Hercun, P.Eng., Mr. Alex Stewart, P.Geo., Mr. Tim Tsuji, P.Eng., Mr. Frank Laroche, P.Eng., and Mr. Carl Diederichs, P.Eng. prepared this technical report (the Report) for Teck Resources Limited (Teck) on the wholly-owned Highland Valley Copper Operations (Highland Valley Copper or the Project), located in British Columbia, Canada.

Teck uses a subsidiary, Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership (Highland Valley Copper Partnership), as the operating entity for the Highland Valley Copper Operations.

| 1.2 | Terms of Reference |

The Report was prepared to support Teck’s news release dated 23 July 2025, entitled “Teck Announces Construction of Highland Valley Copper Mine Life Extension to Proceed”.

Teck commenced the permitting application process for the life-of-mine (LOM) plan described in this Report in 2019. The initial application referred to the mine plan as the Highland Valley Copper 2040 Project (HVC 2040), later changing to the HVC Mine Life Extension Project (HVC MLE). The permits were granted in 2025, and the permitted mine life extension project is the LOM plan in this Report.

Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves are estimated for the Valley, Lornex, Highmont, and Bethlehem deposits.

Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves are reported using the confidence categories in the Canadian Institute of Mining, Metallurgy and Petroleum (CIM) Definition Standards for Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves (May 2014; the 2014 CIM Definition Standards).

The Mineral Resource and Mineral Reserve estimates are forward-looking information and actual results may vary. The risks regarding Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves are summarized in the Report (see Section 14, Section 15, and Section 25). The assumptions used in the Mineral Resource estimates are summarized in the footnotes of the Mineral Resource table and outlined in Section 14 of the Report. The assumptions used in the Mineral Reserve estimates are summarized in the footnotes of the Mineral Reserve table and outlined in Section 15 and Section 16 of the Report.

Currency is expressed in Canadian dollars (C$) unless stated otherwise.

Units presented are typically metric units, such as metric tonnes, unless otherwise noted.

The Report uses Canadian English.

| 1.3 | Project Setting |

The Highland Valley Copper Operations are located approximately 75 km southwest of Kamloops, British Columbia (BC) and 17 km west of the town of Logan Lake, BC.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

The operations are readily accessible by paved highway, including from Vancouver via Highway 1 to Highway 5 (the Coquihalla Highway) to Merritt, and then via Highway 97C to Logan Lake and the Highland Valley Copper Operations. Highway 97C also connects the site to Ashcroft, location of the railway terminal for copper concentrate handling. Services offered at Ashcroft include bulk, break-bulk, and container (forthcoming) handling. Passenger rail services provided by VIA Rail and Canadian Pacific are available in Kamloops. There are three airports within the Thompson–Nicola Regional District, one of which provides commercial services.

The climate is characterized as semi-arid, characterized by warm summers, cold winters, and the lack of a distinct wet season or dry season. Mining operations are conducted year-round.

The mine is located within the approximately 23 km long Highland Valley, at the lower elevation end of the Thompson Plateau in the southern Interior Plateau region of BC, on the eastern slope of the Pacific Coastal Mountains. The Highland Valley is bounded on the west by the Thompson River, and on the east by the Guichon Creek Valley. The mineral tenure area ranges in elevation from 1,000–1,750 metres above sea level (masl) with the highest elevations occurring in the southwestern part of the area. The mining operations are situated at approximately 1,280 masl. Vegetation varies depending on moisture availability, elevation, and aspect, and typically consists of fire-dominated, dry-land vegetation.

The Thompson–Nicola Regional District has a history of development and land use that includes forestry, ranching, and mining dating back to the early 1900s. It currently supports substantial urban settlement, mining, forestry, agriculture recreation, and transportation including several highway and railway corridors.

The Project area is included in the General Resource Management Zone defined under the Kamloops Land and Resource Management Plan, within which mineral development is identified as an allowable land use.

The Highland Valley is a significant area for Indigenous Peoples who have historically occupied the area and continue to use it today. Primary and traditional uses include but are not limited to: hunting, fishing, gathering, other cultural and spiritual purposes, agriculture, and livestock watering. The Highland Valley Copper mine site is located within the unceded territory of the Nlaka’pamux Nation, and the Secwépemc Nation also have interests in the area.

| 1.4 | Mineral Tenure, Surface Rights, Water Rights, Royalties and Agreements |

The mineral tenure area consists of 941 active mineral claims (55,625 ha), 106 active mining leases (3,391.1 ha) and 18 active Crown grants (private mineral holdings; 1,237.9 ha) that collectively cover about 60,254 ha. All tenure is held 100% in the name of the Teck subsidiary Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership. The mineral claims and mining leases are renewed annually, per the BC Mineral Tenure Act. Crown grants are an interest in land as a fee simple estate in ownership. These rights are held in perpetuity by Highland Valley Copper if the assessed property and mineral taxes are paid annually. All required payments were current at the Report effective date.

Surface rights in the Project general area are held 100% in the name of Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership. Additional land acquisition may be required for easements to support the LOM plan.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

Teck currently holds 26 active BC water licences in the name of Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership that have expiry dates ranging from 2026–2053. Water licences are renewed as necessary per the BC Water Sustainability Act.

There are no royalties, back-in rights, payments or other agreements outside of the percentage distributions of the Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership on claims held to cover the Highmont, Valley and Lornex open pits.

| 1.5 | Geology and Mineralization |

The Highland Valley deposits are considered to be classic examples of porphyry copper–molybdenum deposits.

The Project is situated within the allochthonous Quesnel island arc terrane. Intrusions belonging to the Lower Jurassic Guichon Suite are a major component of the Quesnel terrane. Plutonism migrated from west to east during the formation of the upper Triassic to lower Jurassic Nicola Group, with the Guichon Creek Batholith representing the oldest, and westernmost intrusion belt of the Quesnel terrane. The intrusive rocks are spatially related to the volcano–sedimentary units of the Nicola Group.

The Guichon Creek Batholith extends over an approximate area of 60 x 30 km. It is a north–northwest elongated multi-phase intrusion with major compositional variations that evolve from an older mafic margin inward to a younger and generally more felsic core. Contacts between the phases, though locally sharp, are commonly gradational and define an annular zoning with the older phases towards the outer margins of the batholith and the younger phases within the central area. The phases are nearly concentric in plan view. Numerous syn- to post-mineralization porphyritic to aplitic dykes and stocks cut the main intrusive facies with the highest density occurring primarily within and adjacent to the porphyry deposits. The porphyry deposits are hosted either in younger phase rocks, or in dyke swarms and intrusive breccias associated with the younger phase rocks.

The batholith is elongated northward and segmented by major north- and northwest–west-striking faults that are closely related to mineralization. The major northerly-trending structures include the central Lornex fault, the bounding Guichon Creek fault to the east, and the Western Boundary Fault to the west. Northwesterly-trending structures include the Skuhun Creek, Highland Valley, and Barnes Creek faults. Dykes appear to preferentially occupy large-scale tension fractures that have similar orientations to the major fault directions.

Adjacent to the batholith contact, a metamorphic halo up to 500 m wide developed. Close to the batholith contact, assemblages are typical of the hornblende hornfels facies; further out, albite–epidote facies are typical.

Distal alteration includes green sericite, epidote, and chlorite, as veins and as fracture coatings. The type of vein alteration developed can reflect host rock composition; green sericite veins characterise the more felsic Bethlehem, Skeena, and Bethsaida phases, but chlorite (epidote) veins are more common in the earlier, more mafic batholith phases. Moderately to strongly developed distal alteration zones surround each of the five main deposits. Proximal alteration and veining types include a barren core of intense quartz veining, potassic (potassic feldspar and hydrothermal biotite) and phyllic. These are overprinted by late, structurally-controlled argillic alteration.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

The major deposits are located in the centre of the batholith, and include the Valley, Lornex, Highmont, Bethlehem, and JA deposits. All of the deposits except the JA deposit have been, or are being mined; JA remains undeveloped.

Significant copper mineralization occurs in a number of stages. The oldest followed the emplacement of Bethlehem granodiorite sub-facies and coincided with dyke intrusion and breccia formation in the Bethlehem area; the Bethlehem mineralization is dated ca 209 Ma. The second phase, dated at ca 208 Ma, followed emplacement of the Skeena sub-facies and Bethsaida granodiorite sub-facies. The Valley, Lornex, and Highmont systems formed at this time.

Most of the sulphide mineralization is developed in fractures, veins, faults, or breccia bodies. Higher copper grades typically occur where the fracture density is high or where several sets of fracture swarms overlap. The first copper-mineralizing event followed the formation of the Bethlehem facies, and occurred with the emplacement of porphyry dykes and breccias into this facies, forming the Bethlehem deposit. The second, and larger, copper–molybdenum mineralizing event followed the emplacement of the Bethsaida facies and resulted in the formation of the Valley–Lornex and Highmont deposits.

The originally contiguous Valley–Lornex deposit was cut by the late-stage Lornex fault, offsetting the Valley and Lornex deposits by about 3.5 km.

The lateral extents of the Valley deposit are generally well defined, but the deposit remains open locally at depth. Mineralization at the Lornex deposit remains open to the south, southeast and at depth. Beneath the Lornex deposit there is considerable potential to extend mineralization as the high-clay and sericite alteration as well as the higher pyrite content compared to the Valley deposit suggests that the Lornex mineralization is a higher-level expression of the system. The lateral extents of the Highmont deposit are generally well defined except to the east. Mineralization also locally remains open at depth within the Highmont deposit. As the Highmont deposit contains multiple mineralized porphyry centres it is possible for additional porphyry centres to be discovered in the area. The Bethlehem deposit is generally well constrained, with limited depth potential. Jersey North is an occurrence located about 400 m to the north of the Jersey pit, and has been tested with multiple drill holes returning encouraging results. Mineralization remains open to the south of the Iona pit. As the Bethlehem deposit contains multiple mineralized porphyry centres it is also possible for additional porphyry complexes to be discovered in the area. Potential to discover additional porphyry bodies within the mine area remains, particularly beneath areas of Tertiary volcanic or recent glacial cover.

| 1.6 | History |

The Project has a long development and exploration history. Prior to the 100% acquisition by Teck of the Highland Valley Copper Partnership in 2004, the following individuals, joint ventures and companies had Project involvement: Egil Lorentzen, Huestis–Reynolds Syndicate, Bethlehem Copper Corporation, Ltd., American Smelting and Refining Co. (Asarco), Kenneco Exploration, Huestis Mining Company, Cominco Ltd., Highmont Mining Corp. Ltd., Rio Tinto Ltd., Yukon Consolidated, Lornex Mining Company, Rio Algom Ltd., Billiton plc, later BHP Billiton plc, and various iterations of the Highland Valley Copper Partnership (initially Cominco Ltd., Rio Algom Ltd., Teck Corporation, and Highmont Mining Ltd.; later Teck Cominco Ltd., Billiton, and Highmont Mining Ltd., and subsequently BHP Billiton and Teck). Work completed included claims staking, regional geological mapping, prospect identification, induced polarization ground geophysical surveys, drilling, underground development, mining studies, and open pit mining. Mined open pits included the Huestis, Jersey, and Iona pits in the Bethlehem area, the Lornex and Valley open pits and the Highmont open pit.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

Following acquisition of the 100% ownership interest, Teck completed district and prospect-scale mapping, geochemical sampling (soil, rock chip and grab), airborne and ground geophysical surveys, core and reverse circulation (RC) drilling, environmental, geotechnical, metallurgical, and mining studies, metallurgical testwork, and open pit mining.

| 1.7 | Drilling |

As at the Report effective date of 1 July, 2025, a total of 4,127 drill holes (805,749 m) were completed across the mineral tenure area. Of the total drilling, there are 2,805 core holes (682,523 m), 518 percussion drill holes (33,343 m), 55 RC drill holes (4,972 m), eight sonic drill holes (661 m), and 741 unknown drill holes (84,250 m). Unknown methods represent drilling completed for distinct drill programs and overburden delineation or geotechnical instrumentation purposes.

Close-out dates for the databases supporting Mineral Resource estimation vary by deposit. Drilling supporting the Valley estimate was completed between 1966–2024 and totals 748 drill holes (220,099 m); the database was closed as at 22 July, 2024. Drilling supporting the Lornex estimate was completed between 1965–2024 and totals 461 drill holes (104,846 m). The database was closed as at 22 June, 2024. Drilling supporting the Highmont estimate was completed between 1966–2024 and totals 422 drill holes (76,924 m); the database close-out date was 10 August, 2023. Drilling supporting the Bethlehem estimate was completed between 1970–2015 and totals 587 drill holes (154,873 m); the database was closed as at 31 March, 2016.

The RC chips collected in 2015–2016 were logged by geologists following Teck practices, and record mineralogy, alteration, and mineralization styles at 1.5 m intervals.

Currently, geomechanical logging of core holes is performed by core technicians, followed by geological logging and sampling by geologists. Geological logging intervals vary based on lithological, alteration, and mineralization variability, with a minimum sample length of 0.5 m. All significant structural features are recorded regardless of length. Specific gravity and point load tests are conducted approximately every 15 m downhole. Sample intervals are defined by logging geologists, with lengths ranging from 0.5–3.0 m. Once sample tags are placed, the core is photographed dry.

Core recovery across all four deposit areas (Valley, Lornex, Highmont, and Bethlehem) has generally been acceptable, ranging from >88 to >94%. Intervals of low recovery are typically associated with fault zones, pre-mining surface exposure, or blast-related damage.

Historical drill collar surveys were taken by theodolites and total station instruments. Under current practices, drill collar locations are typically recorded using high-precision global positioning system instruments. For angled drill holes, as-built surveys are conducted using total station instruments to ensure accurate collar orientation and positioning. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry is completed over the open pits, from which 3D photogrammetric maps of pit topography are generated. The UAV is also used to provide video footage for mine planning and pit inspections. Laser scanning is used for 3D mapping of pit walls, and to survey geotechnically sensitive areas.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

Currently, downhole surveys are conducted using a Reflex single-shot survey tool. Surveys are typically performed at 60-m intervals on the way into the hole, at the end of the hole, and again at 60-m intervals on the way out, offset from the inbound survey depths where possible, or as permitted by ground conditions.

Grade control at the Highland Valley Copper Operations is managed through systematic blast hole drilling, which provides detailed spatial data to support ore-waste delineation and short-term mine planning. Standardized drill patterns have been employed across the various deposits, with minor adjustments over time to optimize fragmentation, dilution control, and ore recovery.

The orientation and geometry of the porphyry systems vary across the different deposits, influencing drill hole design and sample length representativity.

Since the database close-out dates for the Valley, Lornex, Highmont, and Bethlehem areas, a total of 52 additional core holes (10,792 m) were completed as at 1 July, 2025. The Qualified Person reviewed the available results from this drilling and compared them to the current block model. The results confirm that the observed mineralization widths are consistent with those presented in the Mineral Resource estimate.

| 1.8 | Sampling and Analysis |

RC samples were collected over 1.5 m intervals. Historically, core was commonly sampled as whole core at 3.0 m intervals. Currently, sample intervals vary by core diameter, NQ-diameter core is sampled at 3.0 m intervals, and HQ-diameter core is sampled at 2.0 m intervals. Blast hole drilling is conducted exclusively to support active mining operations and is not used in Mineral Resource estimation.

No historical specific gravity (SG) measurements predating 2010 were identified in the acQuire database. SG data collection commenced in 2010 and continued through 2019 across the four deposit areas. SG determinations were performed by core logging personnel at the Teck core facility using the water displacement method.

Two main primary analytical laboratories provided analytical services, the mine laboratory and the laboratory currently known as Bureau Veritas Commodities Vancouver (Bureau Veritas). The mine laboratory is not independent and is not accredited. It was used as the primary laboratory from the 1960s–2013. Bureau Veritas and its predecessor ACME Analytical Solutions, located in Vancouver, BC, were and are independent; Bureau Veritas holds ISO/IEC17025 accreditations for selected analytical techniques. Bureau Veritas was used from 2013 onwards. The current check assay laboratory is ALS, in North Vancouver, BC, which is an independent laboratory and holds ISO/IEC17025 accreditations for selected analytical techniques.

Sample preparation methods had minor variations between the different laboratories. Samples were typically crushed to 2 mm or 70% passing 2 mm, and pulverized to either 95% passing 106 µm (150 mesh) or 85% passing 75 µm (200 mesh). Analytical methods included:

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| · | Aqua regia leach with atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) finish (Cu, Mo, As, Fe); |

| · | Multi acid or aqua regia digestion; multi-element suite, reported using either inductively coupled plasma (ICP) atomic emission spectroscopy (AES or mass spectrometry (MS); |

| · | Infrared combustion methods reporting sulphur and carbon; |

| · | 5% H2SO4 leach with AAS finish to determine copper oxides; |

| · | 1% NaCN leach with AAS finish to determine copper oxides and secondary sulphides. |

Sample security relied, and continues to rely, upon the fact that the samples were always attended or locked at the sample dispatch facility. Chain-of-custody procedures consisted of filling out sample submittal forms that are sent to the laboratory with sample shipments to ensure that all samples were received by the laboratory.

A quality assurance and quality control (QA/QC) program was in place from 2016 onward. This included insertion of standard reference materials (standards), coarse and pulp blanks, and duplicates into the sample stream. Where a quality control sample was outside allowed tolerances it was reviewed by a quality control specialist who could recommend re-assays and/or other remedial actions. The QA/QC programs adequately addressed issues of precision, accuracy, and contamination.

| 1.9 | Data Verification |

Highland Valley Copper Operations personnel prepare an annual “Resource and Reserve” report that documents the methodologies and data supporting the Mineral Resource and Mineral Reserve estimates for the reporting year. The report includes a comprehensive review of QA/QC and reconciliation data.

Numerous external audits or data collection supervision have been undertaken since 2004; the most recent was in 2025, when both the mine plan and Mineral Resource and Mineral Reserve estimates were audited.

Each Qualified Person undertook data verification in the discipline areas for which they were taking responsibility. No material issues were noted as a result of that verification by any Qualified Person.

| 1.10 | Metallurgical Testwork |

A significant number of metallurgical studies and accompanying laboratory-scale and pilot plant tests have been completed. The majority of the early testwork is no longer relevant due to the deposit areas that were tested being mined out. These test programs were sufficient to establish the optimal processing route. The results obtained supported estimation of recovery factors for the various mineralization types.

Either internal metallurgical research facilities operated by the property owner at the time, or external consultants, undertook the testwork and associated research. The testwork facilities performed metallurgical testing using industry-accepted procedures and to industry-accepted standards at the time the testwork was completed. There is no international standard of accreditation provided for metallurgical testing laboratories or metallurgical testing techniques.

Geometallurgical variability testwork programs were conducted between 2013 and 2023 on mineralization from the Bethlehem, Iona, Valley–Lornex, and Highmont areas to support LOM planning. The testwork was performed at independent laboratories, including SGS in Burnaby and ALS in Kamloops. All testwork data and results from these programs were retained.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

The recovery estimates for the LOM are developed using various distinct recovery models. The current structure of the empirical copper recovery model was first developed in 2012 and is periodically refined to reflect additional operating and advancements in orebody knowledge. The empirical copper recovery model is used prior to the addition of C3 ball mill and the D-Auto SAG conversion in the LOM plan and is based on historical operating data. A separate copper recovery model is developed for the remainder of the LOM, based on testwork to simulate the expected flotation performance of a modified mill circuit. This model is only applied after the completion of the grinding and flotation circuit upgrades. A variable model for molybdenum circuit recovery is used, which is based on bulk feed parameters to the circuit. The recovery forecasts for the LOM are provided in Table 1-1.

The copper concentrate is not expected to have any notable levels of deleterious elements such as arsenic, antinomy, mercury, zinc, and lead, which will provide HVC a competitive edge.

| 1.11 | Mineral Resource Estimation |

Mineral Resources were estimated for the Bethlehem, Highmont, Lornex, and Valley deposit areas. Selective mining unit blocks were set for all deposits at 25 x 25 x 15 m.

Rock types were defined based on the current understanding of geology and mineralization controls.

For the Valley deposit, two copper and two molybdenum grade shells were created. The Valley grade shells were restricted by the Lornex fault to the east and overlying overburden–rock surfaces. Two copper grade and two molybdenum grade shells were used for the Lornex deposit. The Lornex grade shells were also restricted by the Lornex fault hanging wall contact to the west and overlying overburden–rock surfaces. One copper grade shell and one molybdenum grade shell were created for the Highmont deposit. At Bethlehem, copper mineralized domains were modeled for two grade domains, and molybdenum mineralized domains were modeled for four grade domains, two each at Iona and Jersey.

Histograms, log probability plots, and descriptive statistics were used to confirm that the composited sample populations in each estimation domain were approximately stationary. Valley mineralized domains were treated as firm to adjacent domains except for the Avalanche domain, which was treated as a hard boundary. Lornex mineralized domains were treated as firm to adjacent domains except for the hanging wall contact of the Lornex fault, which was treated as a hard boundary. Estimation at Highmont used adjacent domain boundaries as firm boundaries, except for the Waterhole fault, which was treated as a hard boundary.

During Bethlehem estimation, the Late Spud Stock, which is a barren unit near Spud Lake, was treated with a hard boundary to prevent grade-smearing.

For the Valley, Lornex, and Highmont block estimates, density values were averaged and assigned by lithology. For the Bethlehem block estimate, density was estimated using inverse distance weighting to the power of two. For the Valley, Lornex and Highmont block estimates a 5 m composite length for grade estimation was selected, as it was the best compatible length option relative to the 15 m block height. For the Bethlehem block estimate, a 6 m composite length for grade estimation was selected.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

Table 1-1: Metallurgical Recovery and Concentrate Grade Forecasts

| Production Model | Forecast Basis | Average

Metallurgical Recovery/ Grade Forecast |

| Copper recovery | 2025 HVC/2019 MLE models | 89.07% |

| Molybdenum bulk/circuit recovery | 2019 MLE/2021 HVC | 60.77% |

| Copper concentrate grade | 2025 HVC model | 34.9% copper |

| Molybdenum concentrate grade | Fixed value | 51.0% molybdenum |

Note: HVC = Highland Valley Copper; MLE = mine life extension project (LOM plan), dmt = dry metric tonne

Histograms and cumulative frequency distributions were analyzed by grade zone domain to identify high-grade outliers and determine an appropriate capping value for each domain as required. This capping approach was applied for both copper and molybdenum in each domain used in estimation. Most domains were capped.

Variography modelling was completed, and search ellipses for grade estimation were derived from the modelled variograms. Ordinary kriging (OK) was selected as the grade interpolation method for estimation of copper and molybdenum grades using Leapfrog Edge. However, the Valley Avalanche unit grade domains (east of the Lornex fault) were modelled differently, using inverse distance weighting to the second power (ID2), because the Avalanche material is a talus deposit, and it is no longer in situ. All mineralized copper and molybdenum domains at Valley, Lornex, and Highmont were estimated using a two-pass estimation strategy. Unestimated blocks were left as blank grades. Outlier restrictions (high yields) were implemented on the second pass only, and only in the low-grade background domains, to prevent high grade blow-outs. Copper estimation at Bethlehem used five passes, with each pass estimating grades only in previously un-estimated blocks. To prevent over-estimation from high-grade copper outliers, high-grade search restrictions (high yields) were applied. The molybdenum estimation approach used three passes.

At Valley, the number of composites used in the estimation ranged from a minimum of 8–10 samples, and a maximum of 12–25 samples. At Lornex, the number of composites used in the estimation ranged from a minimum of 9–10 samples to a maximum of 16–25 samples, with a maximum of four composites per drill hole for the first pass and five composites per drill hole for the second pass. The number of composites used in the Highmont estimation ranged from a minimum of 9–10 samples, and a maximum of 16–25 samples. The maximum number of composites per drill hole ranged from four per drill hole for the first pass to five per drill hole for the second pass. A minimum of seven and a maximum of 14 composites were used in each estimation pass at Bethlehem.

Block estimates of copper and molybdenum were validated using several methods, including visual validation; comparison between ordinary kriging and nearest neighbour statistics; swath plots; and change of support analysis. No material biases in the estimations were noted.

Drill spacing supporting the Measured Mineral Resource confidence category aimed for ±15% accuracy in quarterly production estimates 90% of the time, albeit modified slightly by also taking into account geological knowledge and mining experience, variography and other statistics, and past reconciliation results. Similarly, the drill spacing recommendations supporting the Indicated Mineral Resource confidence category aimed for ±15% accuracy in annual production estimates 90% of the time, again modified slightly, as it was for the Measured Mineral Resource. The drill spacing recommendations supporting the Inferred Mineral Resource confidence category were based on double the recommended spacings for the Indicated Mineral Resource confidence category.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

Teck uses a copper-equivalent grade (CuEq) for Mineral Resources reporting.

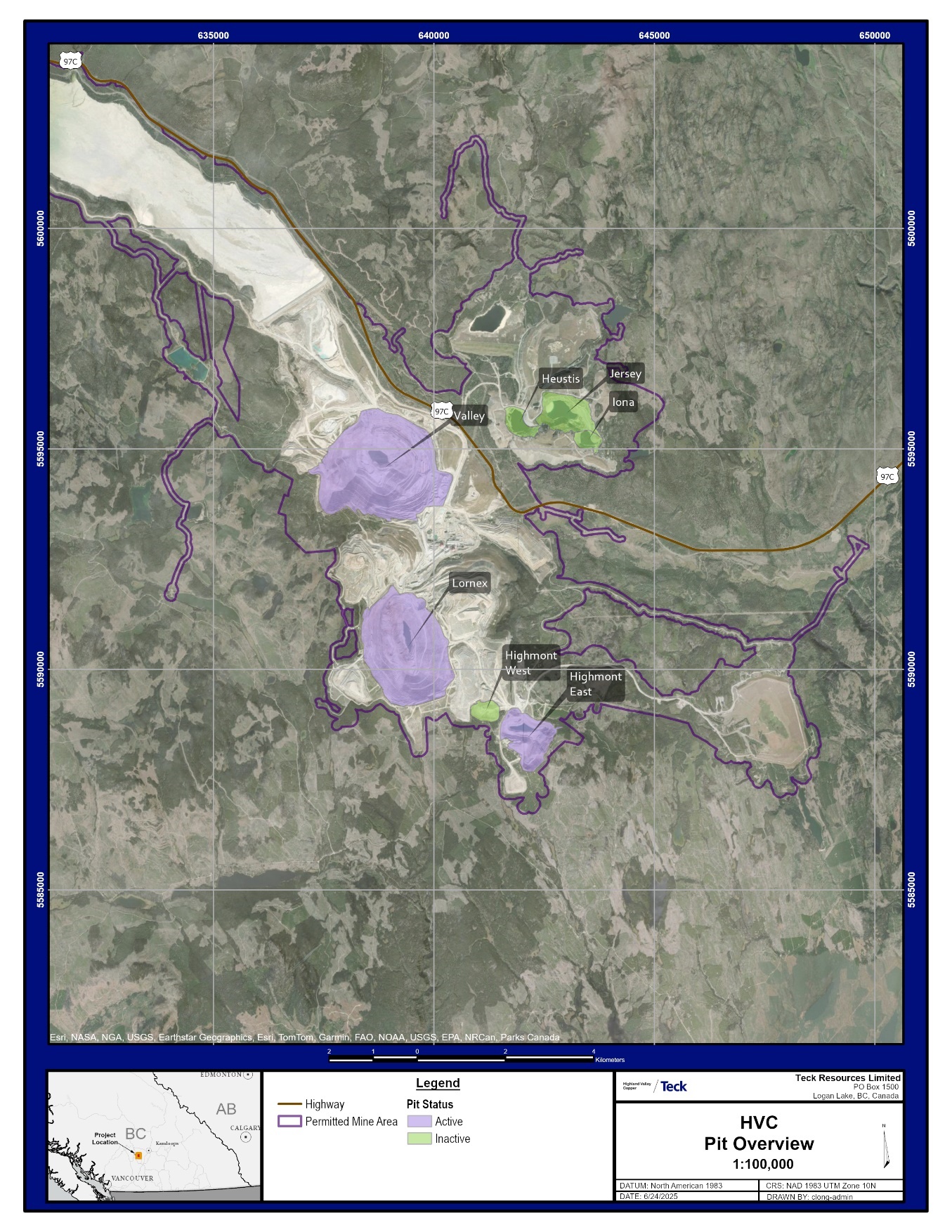

A molybdenum factor is initially determined to represent the economic value of a quantity of molybdenum in the mill feed compared to an equal quantity of copper, calculated in the following formula where charges and costs are expressed in dollars per tonne of payable metal:

Copper-equivalent grade models are then created using the following formula:

| · | CuEq% = Cu% + (Mo% x molybdenum factor) |

The resource-constraining pit shells were based on a Lerchs–Grossmann optimization process using Whittle software, and a set of commodity prices established annually by Teck for Mineral Resources and Mineral Reserves estimation. Potentially-mineable blocks were constrained to claims owned by Teck, limiting the southeastern extent of the Highmont Mineral Resources estimate. Pit shells generated for a revenue factor of 1.0 were used for all areas.

| 1.12 | Mineral Resources Statement |

Mineral Resources are reported in situ, using the 2014 CIM Definition Standards. The Mineral Resources estimate has an effective date of 1 July, 2025 (Table 1-2).

The Qualified Person for the Mineral Resource estimates is Mr. Alex Stewart, P.Geo., a Teck Highland Valley Copper Partnership employee.

Factors that may affect the Mineral Resource estimates include: metal price and exchange rate assumptions; changes to the assumptions used to generate the copper equivalent cut-off grade; changes in local interpretations of mineralization geometry and continuity of mineralized zones; changes to geological and mineralization shapes, and geological and grade continuity assumptions; density and domain assignments; changes to geotechnical assumptions including pit slope angles; changes to cost assumptions; changes to mining and metallurgical recovery assumptions; changes to the input and design parameter assumptions that pertain to the conceptual pit constraining the estimates potentially amenable to open pit mining methods; and assumptions as to the continued ability to access the site, retain mineral and surface rights titles, maintain environment and other regulatory permits, and maintain the social license to operate.

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

Table 1-2: Mineral Resources Summary Table

| Deposit/Area | Confidence Category | Tonnage (kt) |

Grade | Contained Metal | ||

| Copper (%) |

Molybdenum (%) |

Copper (kt) |

Molybdenum (kt) |

|||

| Lornex | Measured | 185,020 | 0.256 | 0.0122 | 474 | 23 |

| Indicated | 177,397 | 0.249 | 0.0108 | 442 | 19 | |

| Valley | Measured | 107,377 | 0.297 | 0.0072 | 319 | 8 |

| Indicated | 356,071 | 0.259 | 0.0075 | 924 | 27 | |

| Highmont | Measured | 3,778 | 0.146 | 0.0196 | 6 | 1 |

| Indicated | 15,697 | 0.153 | 0.0203 | 24 | 3 | |

| Bethlehem | Measured | 7,302 | 0.314 | 0.0042 | 23 | 0 |

| Indicated | 4,536 | 0.237 | 0.0038 | 11 | 0 | |

| Total Measured and Indicated | 857,177 | 0.259 | 0.0094 | 2,221 | 80 | |

| Lornex | Inferred | 79,123 | 0.200 | 0.0107 | 158 | 8 |

| Valley | Inferred | 201,892 | 0.200 | 0.0087 | 403 | 18 |

| Highmont | Inferred | 7,004 | 0.187 | 0.0171 | 13 | 1 |

| Bethlehem | Inferred | 3,510 | 0.258 | 0.0025 | 9 | 0 |

| Total Inferred | 291,530 | 0.200 | 0.0094 | 584 | 27 | |

Notes to Accompany the Mineral Resources Table:

| 1. | Mineral Resources are reported in situ, using the 2014 CIM Definition Standards, and have an effective date of 1 July, 2025. The Qualified Person for the Mineral Resource estimate is Mr. Alex Stewart, a Highland Valley Copper Partnership employee. |

| 2. | Mineral Resources are reported exclusive of those Mineral Resources converted to Mineral Reserves. Mineral Resources that are not Mineral Reserves do not have demonstrated economic viability. |

| 3. | Mineral Resources are constrained within pit shells. Input parameters included: copper price of US$3.80/lb Cu, molybdenum price of US$15.20/lb Mo; exchange rate of C$:US$ of 1.31; copper selling cost of US$0.239/lb recovered Cu; mining costs that vary by deposit, with averages ranging from $3.36–3.83/t mined; administration costs of $2.55/t milled; mill and tailings costs that range from $5.91–9.68/t milled; variable mill recoveries that range from 80.1–92.1% for copper, and variable pit slope angles that vary by deposit and pit, ranging from 7–51°. Mineral Resources are reported at a copper equivalent cut-off grade of 0.10%. The copper equivalency equation is CuEq% = Cu% + (Mo% x molybdenum factor). The molybdenum factor is determined to represent the economic value of a quantity of molybdenum in the mill feed compared to an equal quantity of copper, and is based on a formula. |

| 4. | Numbers have been rounded and may not sum. |

| October 2025 | Page 1- |

|

|

NI 43-101 Technical Report on Highland Valley Copper Operations British Columbia |

| 1.13 | Mineral Reserve Estimation |

The design reserve pits were based on a Lerchs-Grossmann optimization process using Whittle software and detailed phased pit designs. Twenty mine phases (nine Valley phases, one Lornex, four Highmont, and six Bethlehem) were devised to prioritize the higher-grade zones within the mineral extraction plan, while maintaining suitable working widths that would enable high productivity mining sequences using large-scale mining equipment. Mining assumes conventional open pit operations using truck-and-shovel technology. The size of the open pits and the production rates are controlled by site-specific constraints.

The Whittle inputs that provided the design basis included Inferred Mineral Resources and a reduction in selling costs to represent silver and gold byproduct credits received for the copper concentrate. Although the pit designs used these parameters, all of the Mineral Reserve estimates within this Report have been estimated with Inferred Mineral Resources converted to waste and no revenues were assumed to be provided by silver and gold.